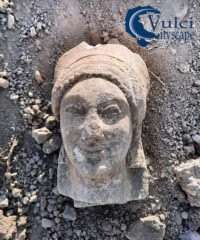

Rare marble portrait of scandal-plagued Victorian lady

The Department for Culture, Media and Sport has placed temporary export restrictions on a rare double portrait of the Victorian sisters by Henri-Joseph François, Baron Triquity. The decision gives a British institution until 13 February 2026 to acquire the work at a suggested price of £280,000.

The Review Committee for the Export of Works of Art and Cultural Objects (RCEWA) recommended the bar because the double portrait is unique among Triquidi’s oeuvre and is “of outstanding significance for research into Triquidi’s provenance, working practices, patronage networks, and commissions for medallion portraits by British families. It is also of outstanding significance for research into the role of women in the Victorian era and for developing ideas about heritage management.”

The son of a wealthy Piedmontese diplomat, Triquiti received a thorough classical education and a profound appreciation of Greco-Roman and Renaissance art and architecture. As a painter, he was an avid art collector and revived in his work classical and Renaissance techniques such as honeysuckle sculptures, portrait medallions, and polychrome patterned marble/stone inlays, which were reinvented for modern tastes.

Triquiti began his career creating decorative sculptures and quickly gained a reputation, receiving important commissions. In 1834, at the age of 30, after only four years of studying sculpture, he was commissioned to create a massive bronze door for the Madeleine Church in Paris. These striking doors are four times taller than Lorenzo Ghiberti’s famous Porta di Paradiso in Florence’s Baptistery and twice as tall as the doors of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, earning him the status of royal sculptor to King Louis Philippe.

After the Revolution of 1848 overthrew the July Monarchy, Triquiti moved to England, where he found new aristocratic patrons. His wife, Julia Foster, was the daughter of the Reverend Henry Wellesley, 1st Earl of Cowley, later British Ambassador to Paris. Cowley and his brother Gerald Wellesley, master of Windsor College, commissioned several sculptures and bas-reliefs and introduced his work to the highest levels of society. Queen Victoria herself purchased the sculpture from Triquiti and presented him with his ivory Sappho and Cupid In 1852 she celebrated the birthday of her beloved husband, Prince Albert. After Prince Albert’s untimely death in 1861, she commissioned Triquiti to design a monument to Prince Albert, and later designed the intricate inlaid marble wall panels and reliefs that decorate the Albert Memorial Chapel at Windsor Castle.

Double portrait of Florence and Alice Campbell is Triquity’s version Imago blinked.a portrait on a round shield, used in ancient Rome to depict images of revered ancestors, gods, and celebrities. They inspired Renaissance tondo painting or sculpture. Triquiti’s innovation lay in transforming the ancient medallion-like background into a deeply concave shape.

Double portrait of Florence and Alice Campbell is Triquity’s version Imago blinked.a portrait on a round shield, used in ancient Rome to depict images of revered ancestors, gods, and celebrities. They inspired Renaissance tondo painting or sculpture. Triquiti’s innovation lay in transforming the ancient medallion-like background into a deeply concave shape.

It is hoped that the acquisition of this work by a UK institution will allow for further research, leading to a greater understanding of the artist’s method and practice. Triquiti’s work also provides a tantalizing opportunity for further research on Victorian women.

The focus of the sculpture is the young sisters Florence and Alice Campbell. It was commissioned by the girl’s father, Robert Tertius Campbell, an Australian businessman known for introducing innovative farming techniques to his Buscot Park estate in Oxfordshire.

The son of a merchant, Robert Campbell made a fortune in gold and moved his family to England in 1852. He invested heavily in climbing the social ladder, buying several country estates and city mansions, and educating his children in aristocratic pursuits. In 1857 he hired a sculptor favored by Queen Victoria to create portraits of his two daughters.

Florence, the daughter in the portrait, began following her father’s master plan by having a high-society wedding to a dashing British officer in 1864, when she was 19. But the marriage faltered. Her husband was a chronically unfaithful and alcoholic, and seven years after their lavish wedding they eventually separated over her father’s disapproval. He died from an alcohol-induced vomiting of blood just weeks after their official separation.

There are those in her father who would long for something as simple as a separation that he described as “morally offensive.” Florence began a relationship with the doctor they sent her to in an attempt to “cure” her of her desire to divorce her husband. To such luminaries of the Victorian era as Benjamin Disraeli and Florence Nightingale, he was a charlatan. She is 25; he is 62. Already married. Her husband’s death had left her with independent wealth, so she ignored her father’s threats to disown her, and she dove headlong into the affair, even being caught having sex with him in the living room of her lawyer’s house, exposing herself to vicious gossip to the point where she was ostracized by society, her family, and even shopkeepers who refused to supply such a scandalous family.

The relationship eventually ended after she suffered a miscarriage and nearly died. In 1875, Florence remarried Charles Bravo, a barrister of legal age. The marriage was an absolute disaster as well. He tried to control her money, isolated her from friends, teamed up with his mother to prevent her from traveling, threatened suicide, beat her and insisted she get pregnant again immediately after a miscarriage. Five months after their marriage, he died of severe abdominal pain. An autopsy revealed that the cause of death was antimony poisoning.

Enter Scandal No. 3. The gossip now is that Florence may have poisoned her husband, and of course all the past gossip about her separation from her first husband and her affair with a doctor old enough to be her grandfather has resurfaced in the tabloids. She must testify for three days at the second trial, answering questions about her past sex scandals. Ultimately, there was zero evidence linking her to the poisoning, and considerable evidence that her husband poisoned himself, but the stain was indelible and ruined her life. She sold her house, fled London and moved to a secluded spot in the countryside, where she effectively became a closeted person and died of alcoholism at the age of 33.

The Charles Bravo case was such a scandal that a century after the event it is still the subject of discussion in three Agatha Christie novels, The Ordeal of Innocence (1958), The Clock (1963), and Elephants Can Remember (1972).

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

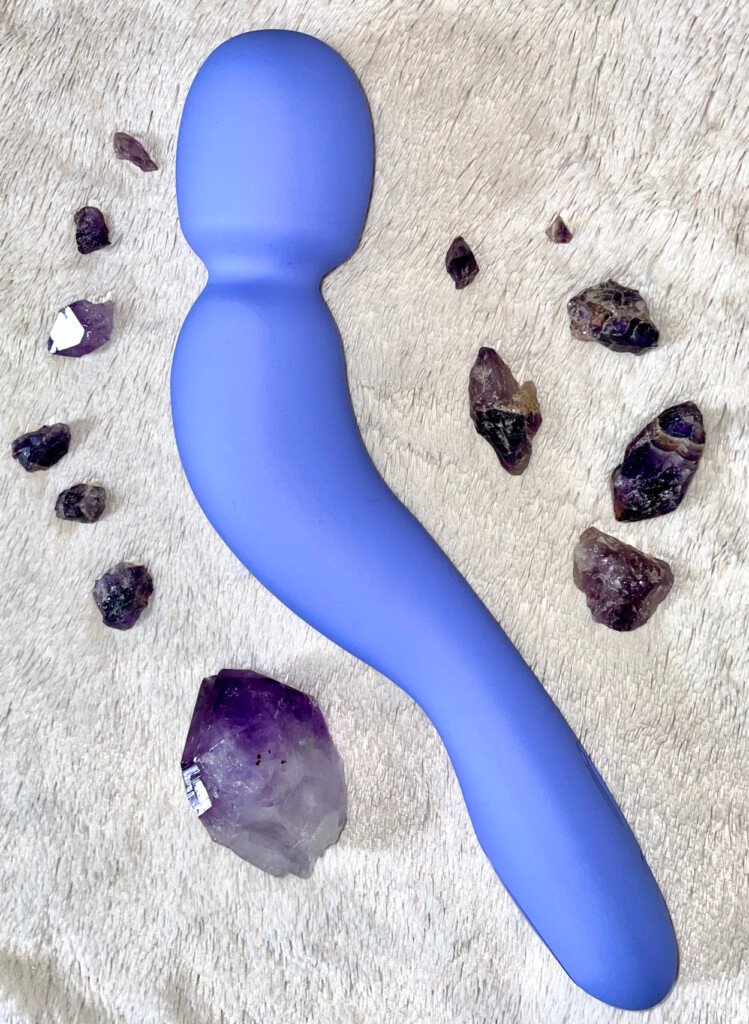

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips