Kenzo Tange: Japan’s most influential architect

Kenzo Tange is the first winner of the Pritzker Award and is undoubtedly one of the most influential architects of the 20th century. Inspired by the creations of Le Corbusier (born Charles-édouard Jeanneret), Tange’s work strikes a balance between modernism and traditional Japanese aesthetics.

On the 20th anniversary of his death, we look back at the lives and times of the people responsible for iconic works, such as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, Yoyogi National Stadium and St. Mary’s Cathedral.

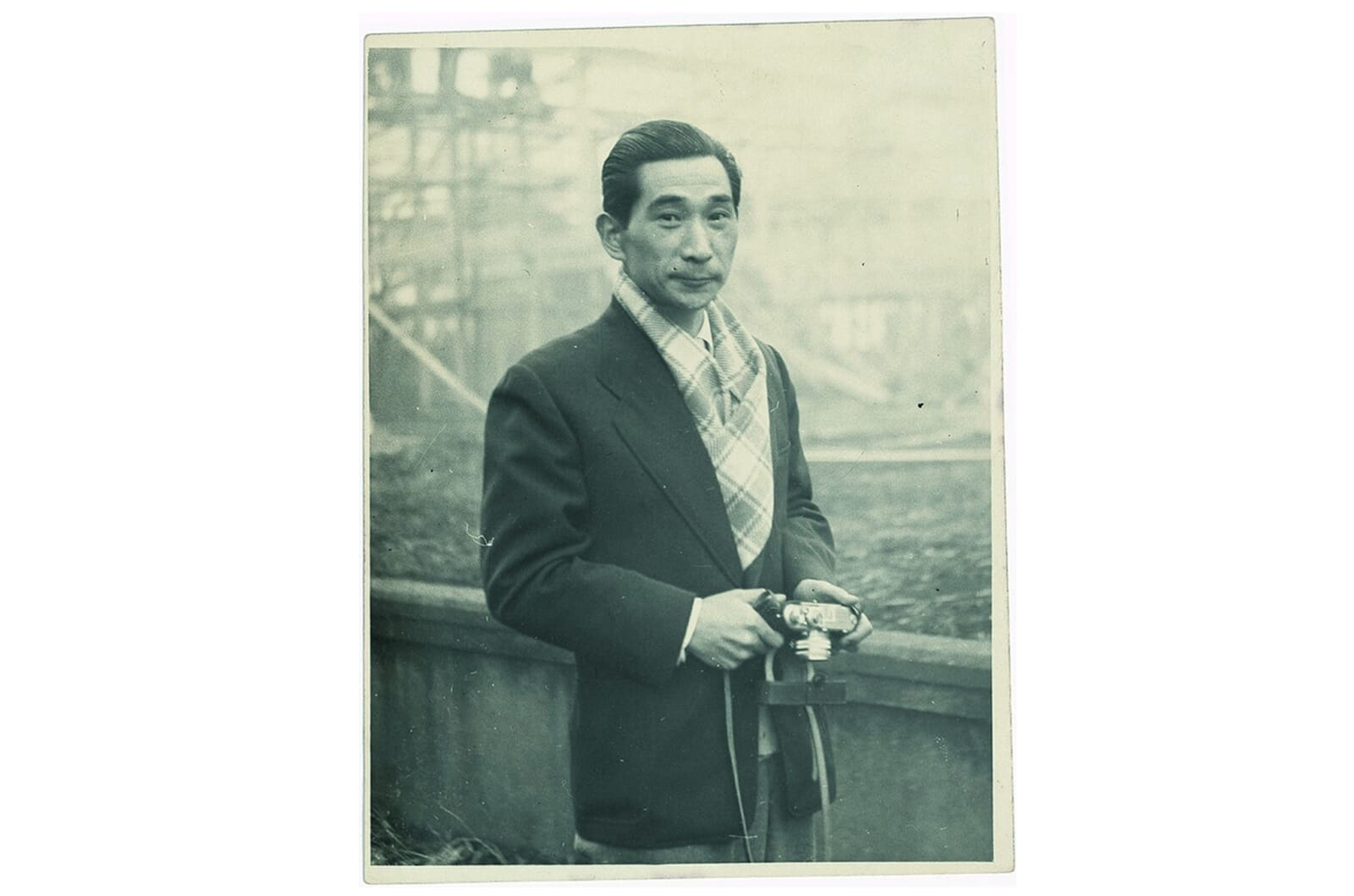

Kenezzards C. 1953 | Wimedia Commons

Kenzo Tange’s background

Tange was born on September 4, 1913 in Sakai, Osaka Prefecture, but he spent his early years in China due to his father’s work. The family moved back to Japan in 1920 and settled in the port town of Imabari, Shikoku Island.

Ten years later, Tange went to Hiroshima to study in high school. It was the first time he saw Le Corbusier’s proposal to the Soviet Palace, which was rejected in 1932. The teenager then enrolled in the Department of Architecture at the Imperial University of Tokyo.

After graduation, Tange worked in the architectural design office in Kunio Maekawa. Maekawa was a former student of Le Corbusier and was a key figure in the development of modern Japanese architecture after World War II. However, this will be his protégé, and he will continue to be the country’s leading architect.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

One of Tange’s earliest and most famous projects was the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, which opened on April 1, 1954. The idea of building a peace memorial site and protecting buildings is located near the ground zero of the bomb explosion in the Atomic Park, from the American Park Planner, from the American Park Planner tam tam tam tam tam tam tam tam delling for seven years. In 1949, an international design competition with 132 entries was held. Tange’s proposal was chosen as the winner.

The North-South Peace Axis includes the monument of the attack victims, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and the bomb dome – Hiroshima Prefecture Industrial Promotion Office, Czech architect Jan Letzel designed it in 1915 as an explosive bomber, but was still subjected to nuclear weapons, and suffered from the attitude of nuclear weapons. The website is visited by more than 1 million people every year.

“After a hard work, he decided to use the idea he had put forward on the back of his cigarette backpack,” Sachio Otani, who assisted Tange, told the project Chugoku Shimbun. “According to the incident, the cigarette brand is called ‘Peace’. The design became a prototype of the park and featured the Anomic Bomb dome, consistent with the A-Bomb victims and the Cenotaph of the Peace Memorial Museum, a remarkable idea to use the A-Bomb dome as a symbol of atomic bombing and the Hiroshima’s “flag.”

Yoyogi National Stadium

By the early 1960s, Tange was considered the “west Japanese architect in the West.” He and his students lead the metabolic movement, which sees buildings and cities as adaptive organic entities capable of regeneration and growth. Influenced by the city’s prosperous population and growing demand, Tange proposed the “Tokyo 1960 Plan”.

Embodying the ideal of metabolic movement, it requires the establishment of a new spatial order in the form of linear megastructures and interlocking loops on Tokyo Bay. Despite impressing the Japanese and international audiences, it is a utopian plan that is more symbolic than practical. However, it is indeed the predecessor of Tange’s later works, including the Yoyogi National Stadium built for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

It was the venue for swimming at the 1964 Olympics, as American teenager Don Schollander became one of the biggest stars in the Olympics with four gold medals. It also hosted diving while the attachment was played in basketball. When Tange won the Pritzker Award in 1987, the citation described it as “one of the most beautiful buildings of the 20th century.” At that time, the highly tensioned hanging roof structure was seen as groundbreaking. For more than 60 years, it remains an eternal architectural miracle.

“It’s kind of like a miracle,” Professor Souhei Imamura, who teaches architecture at Chiba Polytechnic Institute, told Huge. “It combines structure, form and function. Each structure is unique, they are unique. Dynamics were needed at that time because Japanese society wanted to change, evolve. These Olympics needed dynamics, too.”

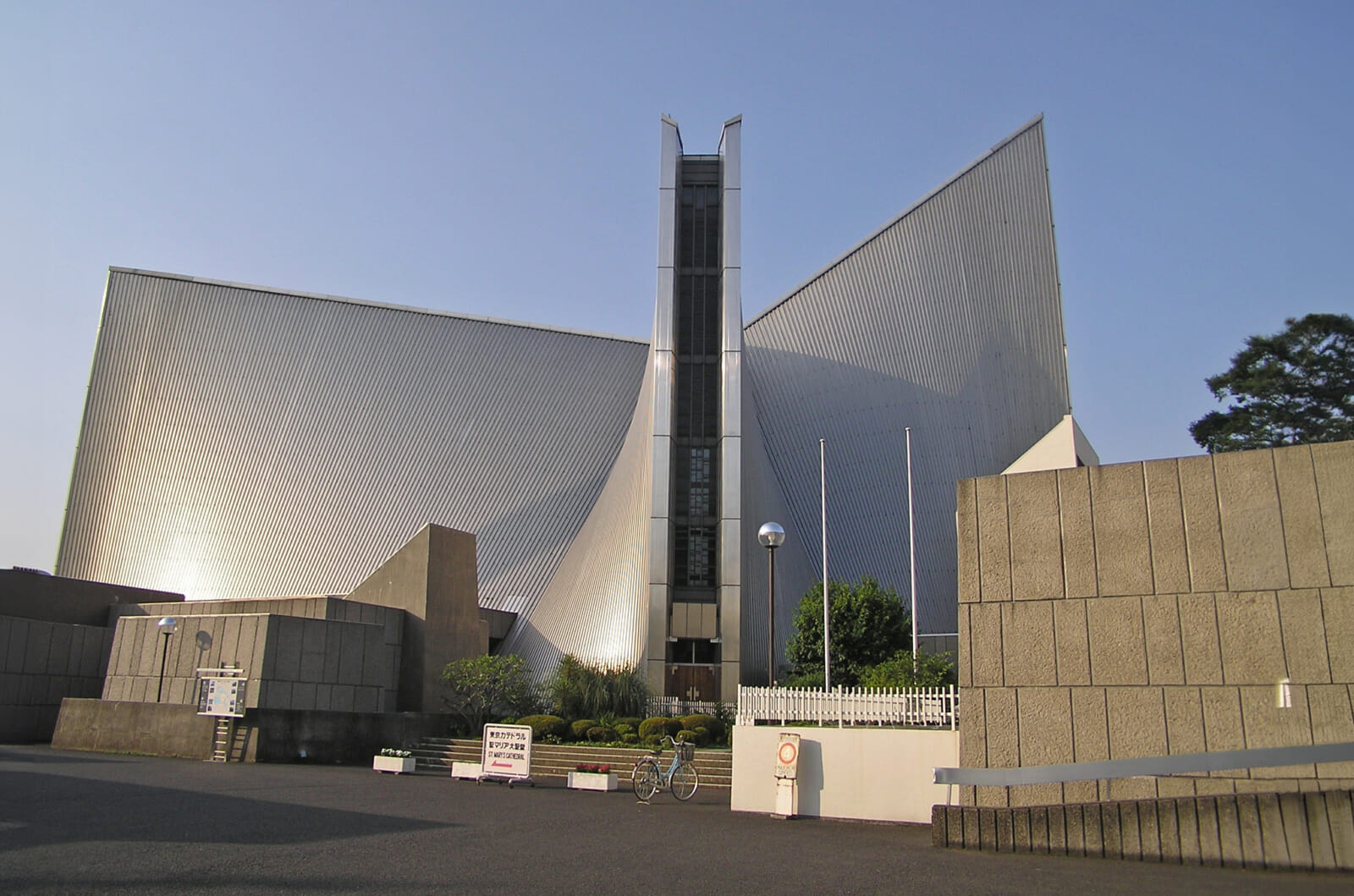

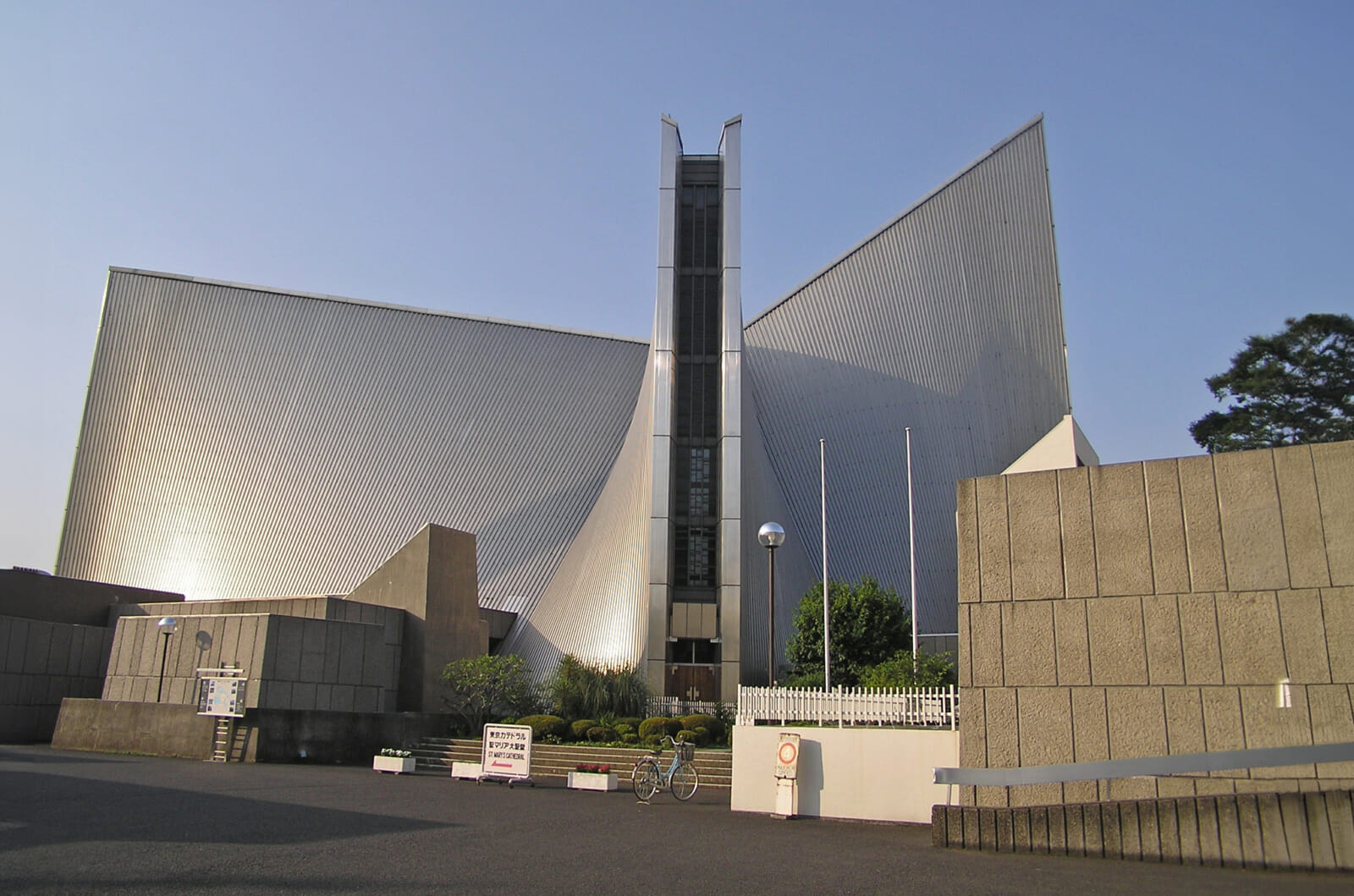

St. Mary’s Cathedral in Tokyo

Other famous projects

Less than two months after the Olympics, another famous building in Tange was completed. The St. Mary’s Cathedral in Tokyo consists of concrete covered with stainless steel and eight curved walls that form a large cross. This is a replacement for the Tokyo Cathedral (Gothic style built in 1899), survived the Grand Canto earthquake in 1923, but was destroyed in the Tokyo airstrike of World War II.

A match was held between his mentor Maekawa and Yoshiro Taniguchi, another star architect at the time. Tange’s winning entry, which is the only cross, is It is said that Assessed by the Pope. However, this is not what everyone likes, architectural historian David Stewart illustrate“The less said about the Tokyo Cathedral.” In 1970, Tange was awarded the Medal of St. Gregory for his design in the cathedral.

In the same year, the Japan World’s Expo was commonly known as the Expo 70’70, and was held in Osaka. Tange and Uzo Nishiyama were appointed as the event’s chief planners, which proved to be a huge success. Other notable domestic structures created by Tange include the Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center in Ginza, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building, the Juku Park Tower and the Fuji Broadcasting Center, which are regarded as symbols of Odaiba.

Outside Japan, Tange may be known for participating in the reconstruction of Skopje, now the capital of North Macedonia, which was then part of Yugoslavia. In Asia, he also designed the Pakistan Supreme Court building, the Philippines’ 68-storey mixed use exploration Primea Tower, Singapore’s indoor stadium and some of Singapore’s skyscrapers that define the city’s central business district’s skyline.

Kenzo Tange’s Death and Legacy

Kenzo Tange died of heart failure on March 22, 2005 at the age of 91. He is widely regarded as the most influential figure in post-war Japanese architecture, inspiring several well-known figures in the industry, including Japanese National Stadium designer Kengo Kuma. “Kenzo Tange and the buildings he designed were one of the reasons I became an architect.” explain Kuma. “The most important thing is that I think I’m influenced by his approach.”

In addition to the Pritzker Award, Tange has won several other awards, such as the Royal Gold in 1965 and the AIA Gold in the second year. He is an architect, teacher and urban planner, and a visionary man who leads the metabolic movement. The legendary designer once said: “There is a strong need for symbolism, which means that architecture must have something that attracts the human heart.” This is exactly what his work does and continues to do.

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

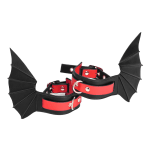

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips