Explore the extraordinary “underground temple” outside

Japan and its major cities were built to withstand. As a country known for experiencing various natural disasters, especially earthquakes and typhoons, its engineering and infrastructure have adapted and evolved to accommodate nature’s extremes. Many skyscrapers are equipped with shock absorbers to counteract seismic vibrations, while underground, out of sight, a labyrinth of vast tunnels waits, ready to channel almost unimaginable volumes of water should flooding occur above ground.

Today, those keen to explore this hidden temple of cold concrete can do so (when it’s not operating, of course).

necessary labor

Underground drainage channels in the periphery of metropolitan areas are among the largest underground flood diversion structures in the world. It is located an astonishing 50 meters underground and stretches 6.3 kilometers through tunnels beneath the city of Kasukabe in Saitama Prefecture, north of Tokyo.

Completed in 2006 after 13 years of construction, the massive structure exists to protect Tokyo and the surrounding area from the damage caused by heavy rains, typhoons and river flooding – problems that have plagued the region for centuries, but These problems are exacerbated by rapid flooding. urbanization. A feat of engineering, it is a vast underground passage of concrete tunnels connecting five vertical shafts, some of which are over 30 meters in diameter. At one end is its most visually striking feature: a cathedral-like cistern the size of a large aircraft hangar. Supported by dozens of majestic pillars, it resembles a long-abandoned stone temple dedicated to the destructive power of nature.

The facility operates about seven times a year, diverting excess rainwater into the Edo River. In 2015, the underground system set a record by diverting and discharging about 19 million cubic meters of water during the 17th and 18th typhoons of that year. For context, one cubic meter of water weighs one ton.

How does it work?

The process begins with a series of small and medium-sized rivers on the surface, including the Ootoshifurutone, Komatsu, Kuramatsu and Naka, and a waterway known as Waterway 18. When heavy rains cause these bodies of water to overflow, the excess water flows into four of the five aforementioned cylindrical underground shafts, which are positioned to collect floodwaters.

From here, the water travels through underground tunnels to Shaft No. 1, sometimes affectionately referred to as the “Megashaft.” From this huge cylinder, flows into the underground cathedral, also known as a pressure-regulated tank, which reduces the force of the water. Thereafter, a terminal drainage pumping station pushes the water through six sluices into the larger Edo River and eventually into Tokyo Bay.

If this all sounds a bit complicated, imagine five barrels connected to each other by a hose. As the first four buckets are filled, water passes through the hose until it reaches the fifth and final bucket. The water is then directed into a larger tank where it is safely released via a pump. Now imagine if these buckets were made of concrete and were over 60 meters tall, 14 meters taller than the Statue of Liberty.

take a tour

One thing about the underground drains on the outskirts of the metropolis: words can never do it justice. Any measurement or reference to the volume of water cannot be translated into an accurate image in the mind’s eye.

Thankfully, we don’t have to just imagine it. Tours are available every day, including Saturdays, Sundays and holidays (except during year-end and new year periods and during facility inspections or operations), and visitors can choose from one of four different itinerary options.

The first and most popular of these is the 55-minute underground temple tour, or if you’re feeling less poetic, the “pressure-regulated water tank” option. Featuring huge concrete towers, this 18-meter-high cave has a stunning ambience of symmetry and quiet, perfect for taking incredible photos. Other tour options also include a visit to the surge tank, but with additional sections added such as Shaft No. 1, the pump room and the large impeller behind the surge tank.

All of these tours include the option to visit the facility’s exhibition room, where the operation of the spillway is explained through small-scale models and the philosophy behind its construction is conveyed – to tame floods rather than fight them. A short film. It’s a good idea to keep your smartphone handy, too, because there’s a free augmented reality app that lets you subtly see the system filling with virtual water while you stand in it.

Please note: There is information material in English explaining the history and inner workings of the underground drainage tunnel, but the tour guide will explain what you are seeing in Japanese. While this does not impact the experience of the Underground Temple Route as it is very simple, as a safety measure some of the more erratic tours may result in tour groups returning without a Japanese speaking group member.

More information

The surge tank is located under Kasukabe City, which is approximately 32 kilometers from central Tokyo and can be reached by train.

For more details on where to go, tours and reservations, visit the facility’s official website.

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

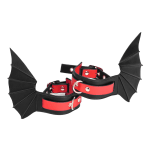

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips