A conversation with Tokyo tattoo artist Keisuke Hirata

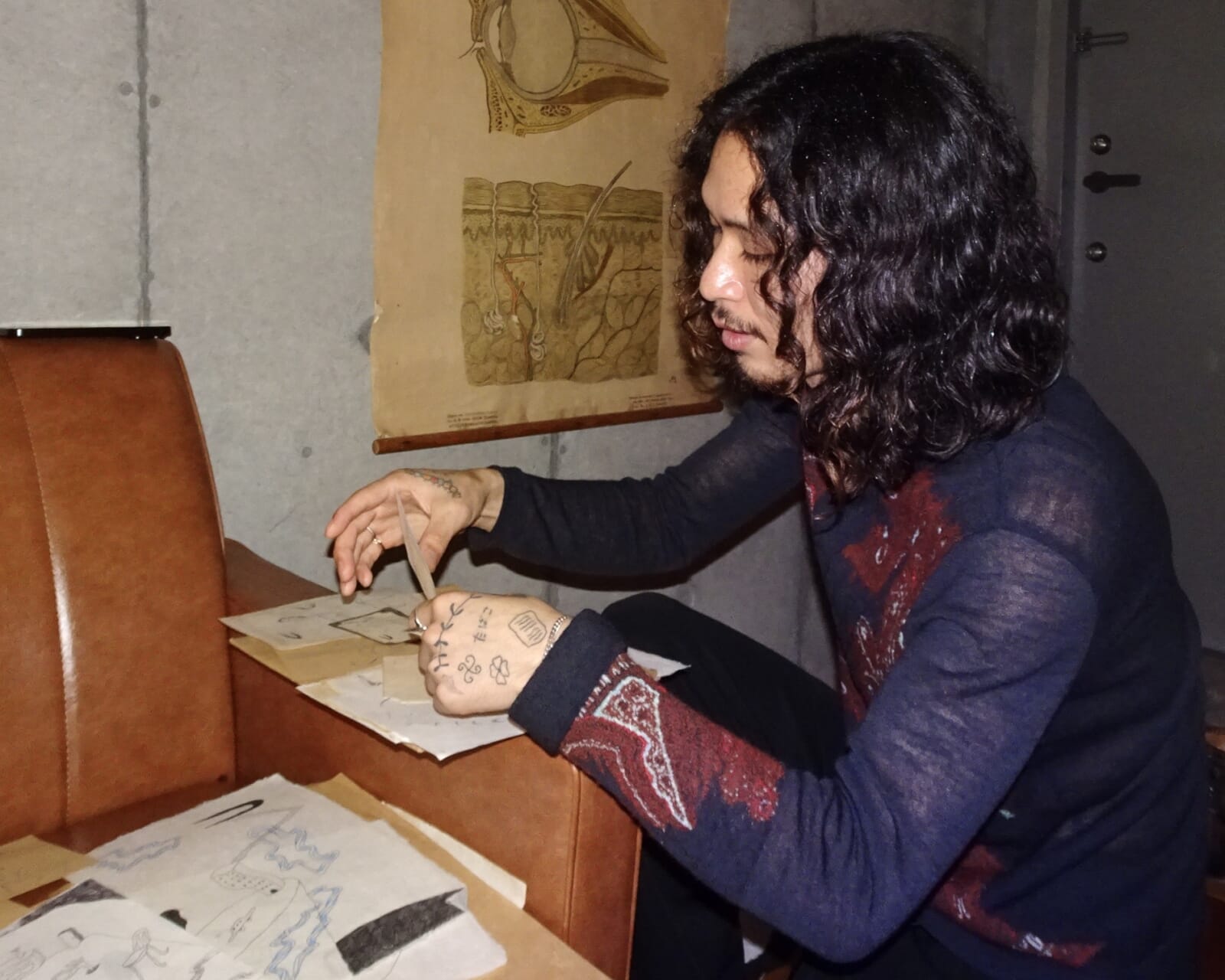

Keisuke Hirata sat across from me on a low stool. He was wearing a see-through cardigan today. The ink artwork on his arms is visible through the fabric, which ripples with deep purple and bruised red, occasionally interrupted by bursts of light blue.

The air around us smelled of tobacco smoke and burning candles, with something woody and earthy about it – maybe cedar. It clings to the room, familiar. To my right is a tattoo bench, with trays of ink bottles and sterilized needles gleaming in the silence.

This is Keisuke Hirata’s studio, Flat Tattoo Room, where graffiti is permanently inked on living skin. Here, he expertly blends interesting designs with traditional tattooing techniques, earning him accolades as one of Tokyo’s emerging tattoo artists.

Keisuke Hirata

Hirata’s voice was soft even though there were several packs of cigarettes scattered around the room. The plant leaned toward the weak afternoon sun, its leaves brushing against the windowpane, as if waiting for his next words.

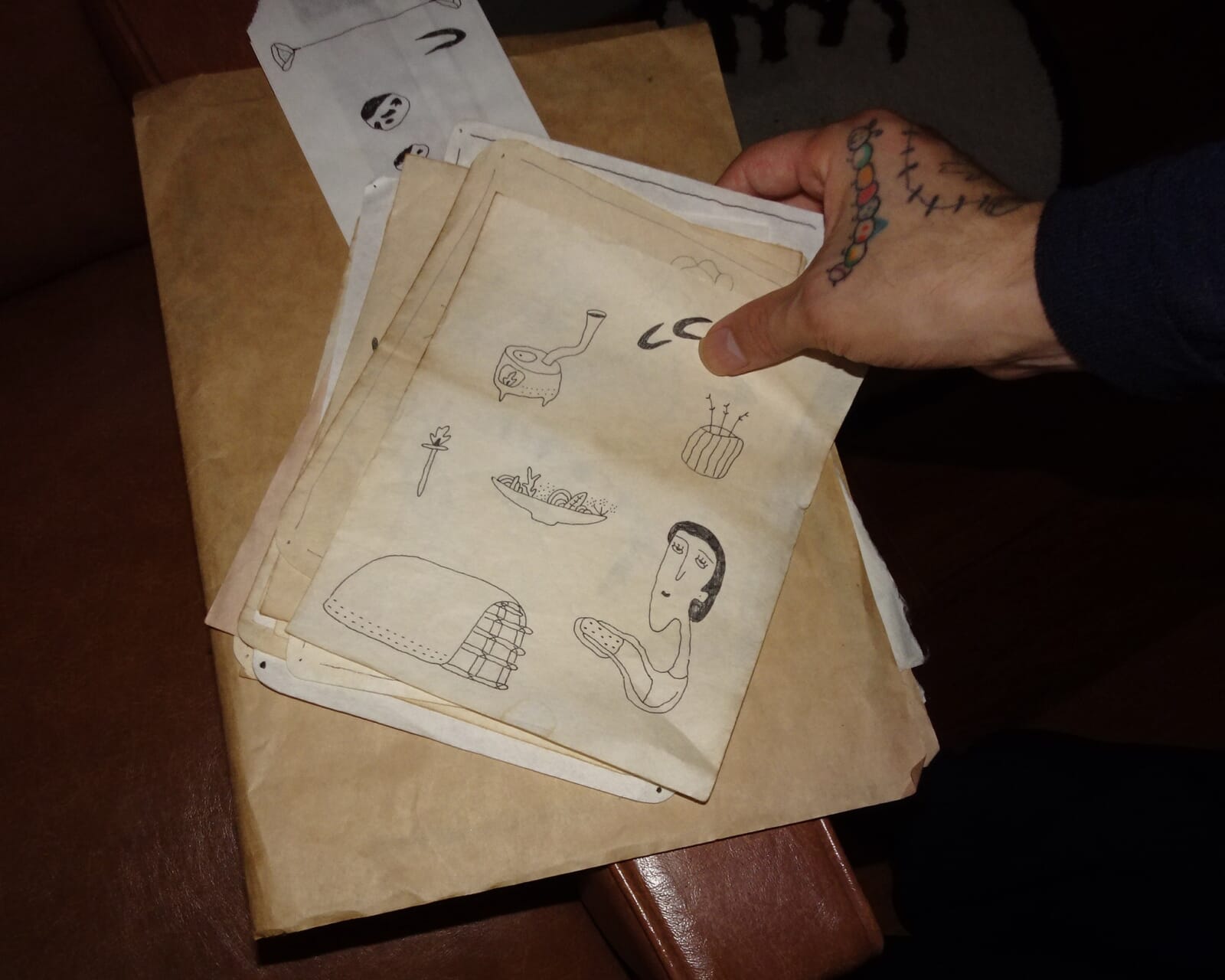

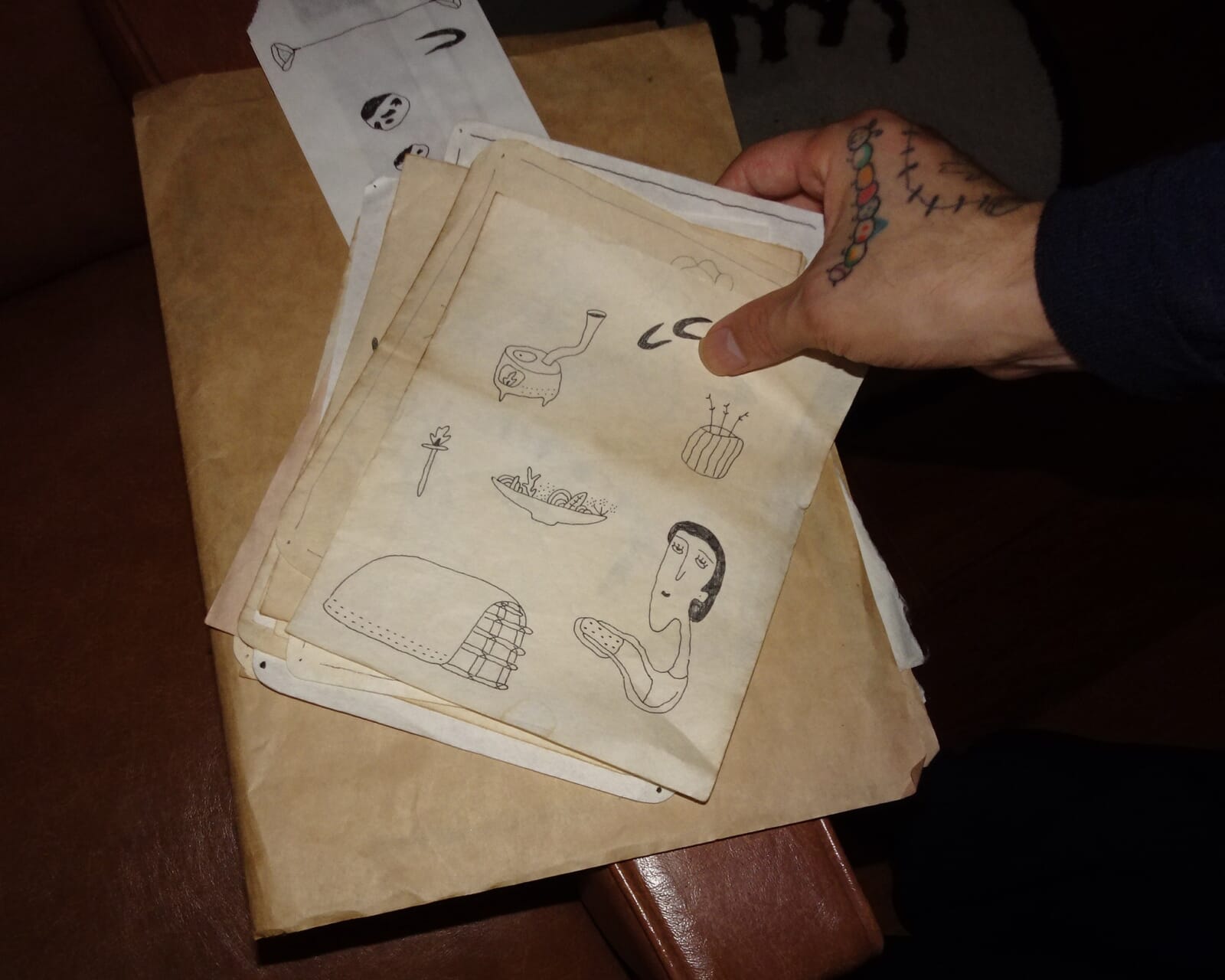

The surprising tenderness Hirata exudes is reflected in his tattoo style. As a stick-and-poke artist, he works by dipping a needle into ink and pressing it into the skin with gentle hands. His works are light, whimsical, almost surreal, like they come from a strange dream. The walls of his studio are a patchwork of these whimsical sketches: a man transformed into a flower, a leaning building, a globe sprouting from a tree. Each one looks like it was plucked from a daydream, or perhaps a napkin sketch made with coffee.

This is in sharp contrast to the tattoo techniques he has grown up with. He started working in his hometown of Asahikawa, Hokkaido, about four years ago before moving to Tokyo. Asahikawa is Work Territory – Bold, thick lines, traditional Japanese tattoos. The dragon coils into a ferocious pose, and the tiger stalks along the arm. A tattoo that symbolizes strength and masculinity.

“You’ll see gangster Everywhere is covered in these tattoos. Wahori did have its own charm, but after a while I started getting tired of seeing the same thing,” he says. “I wanted something different, something softer, the opposite of all the rigidity. ”

I asked him about his choice of hand poking rather than using a machine. “It’s intimate,” he said. “Carefully type it line by line. There’s a feeling of being close to it. It’s not just about getting a tattoo and saying ‘goodbye.’ It feels more human.”

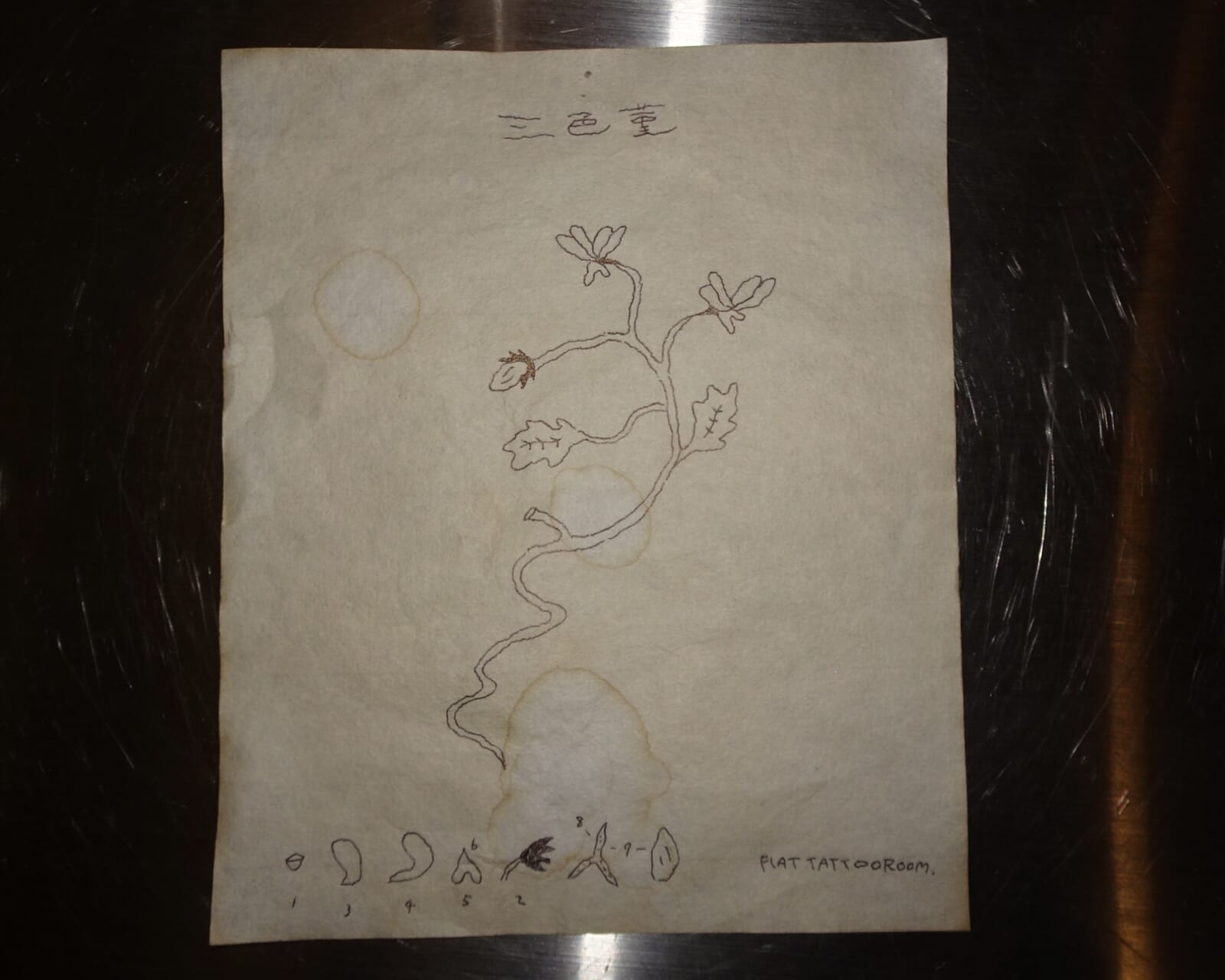

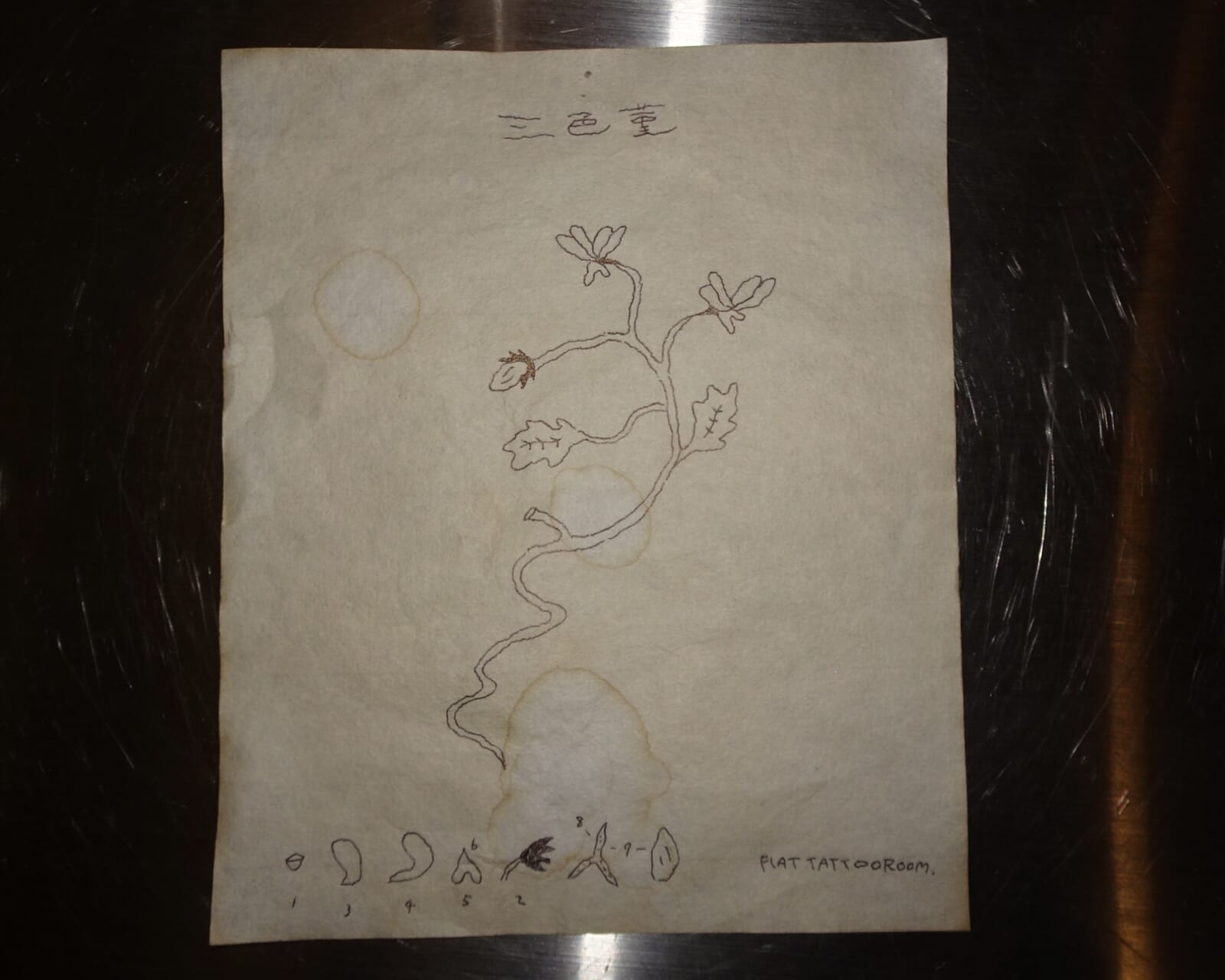

Hirata’s design

In fact, my first tattoo was designed by Hirata. The piece feels like an extension of myself, with slightly marbled lines that blend seamlessly with my skin rather than being solid black.

In the winter of 2022, I walked into his studio with a design: I told him I wanted a portrait inspired by a self-portrait of Jean-Michel Basquiat. When I arrived, he sat me down on a cream-colored cushion and placed six hand-drawn sketches on a low table. Each piece is a subtle exploration of my ideas, capturing the essence of Basquiat while incorporating Hirata’s signature touches – elegant dots and flowing curvatures soften the edges, making the designs unmistakably his of. I chose the one decorated with his signature little flowers.

The art he creates has a very personal feel and is tailor-made for each individual. This is more like an artistic exchange with friends than a transaction. To this day, I still have the paper he used as a tattoo template—I keep it in my wallet as a souvenir. The small flower tattoo on his left cheekbone wrinkles slightly with a smile when I mention it to him.

I pressed the most memorable tattoo on his body, expecting a profound story. But he surprised me. “I got tattoos of cakes and cookies because people had a delicious dessert the day before.”

I blinked and was silent for a moment, not sure if he was joking. But the gleam in his eyes said otherwise. “I love seeing that,” he continued. “Do whatever feels right at the moment. This kind of freedom is rare in Japan.”

Tattoos are slowly gaining popularity in Japan, but the stigma remains deep-rooted. The negative connotation is a remnant of the association between tattoos and the yakuza or Japanese mafia. Even now, public bathrooms, gyms, and even beaches have clear signs: Tattoos are not allowed.

Hirata understands this cultural tension but approaches his work in a refreshingly subtle way. He’s not out to shock or provoke; rather, his goal is to promote quiet acceptance and recognition that we all carry stories on our skin, whether inked or invisible.

“Things are slowly changing,” he said. “Tattoos always spark opinions. One person loves it, another hates it. That’s normal. I just want people to relax. We are all on different paths and everyone expresses themselves in their own way. Why Why not let these expressions become reality?”

His carefree approach underscores a major cultural shift: As tattoos become more normalized, they begin to transcend past associations. He is part of a new wave of artists in Japan who view tattoos as personal expression rather than rebellious statements. He hopes that one day tattoos will be considered an option.

by @flattattooroom

Despite Hirata’s casual attitude and whimsical style, in many cases the simplicity of Hirata’s designs belies their emotional depth. He draws inspiration from artist Shibusawa, whose work evokes the haunting beauty of Victorian flowers from children’s fairy tales. The blooms appear to be just flowers at first, but the more you look at them, the more disturbingly seductive they become, echoing the Victorian era’s flirtation with taboo. “There’s an almost sadistic, sensual way in which Shibusawa paints flowers,” he said. “I’m drawn to that tension, the way desire dances on the edge of pleasure and pain.”

Lately, he’s been painting sofas. For him, a simple piece of living room furniture became a symbol of the vicissitudes of family life and the search for romantic comfort and support. Over the past few months, he’s painted a number of these: springy sofas, distressed sofas, and even a sofa that turns into a door. The door sofa has a gentle curvature that seems to defy the laws of physics and float in mid-air like a cloud. Dotted lines outline its shape and soften the edges.

“I was in this relationship and then another woman came along and wanted an open, three-way relationship. We tried for about a month. But then I realized, I hated it,” he said. “After we broke up, I started painting the couch. I used it to express the situation – turning half of the couch into a door, symbolically. Half comfort, half escape.” His art, like him ‘s human relationships, drawn from the often puzzling moments of everyday life. The couch, of all things, became a vessel for his emotional turmoil.

Hirata’s flowers

As with Hirata’s work, Tokyo’s evolving tattoo scene exists in a space of overlapping tensions. Once a symbol of rebellion or danger, tattoos are slowly shedding these connotations, finding new expression and acceptance in the hands of artists like him. However, they still live in a realm of illegality and taboo, at least for now. It is this contradiction—the almost contradictory fusion of the taboo and the everyday—that attracts Hirata.

“I think it’s this in-between space that fascinates me,” he says. “Opposites – love and hate, beauty and decay, pain and pleasure, the desire to live and the desire to die – they are closer than we think. Where they touch, things get interesting.”

In this quiet studio in Yoyogi, acceptance and longing are expressed in the fine lines etched bit by bit into living skin.

Follow Keisuke and his work on Instagram @flattattooroom.

flat tattoo studio

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips