Anglo-Saxon gold and garnet jewelery found in Lincolnshire –

In 2023, two metal detectors discovered five pieces of Anglo-Saxon gold and garnet jewelery on a hillside near Bain Donington, Lincolnshire, England. Dating to the 7th century, they were found scattered within a 20 to 30-foot radius in plowed soil, indicating that they had recently been plowed and plowed. The assemblage is the largest known assemblage of gold and garnet jewelery in Lincolnshire.

The largest jewel in the group is a D-shaped pendant set with garnets and decorated with gold bands and gold filigree inserts. It has damage to the upper right corner and is very finely crafted, unlikely to have been caused by agricultural activity. More likely, it was done using tools during the garnet setting or before burial.

The largest jewel in the group is a D-shaped pendant set with garnets and decorated with gold bands and gold filigree inserts. It has damage to the upper right corner and is very finely crafted, unlikely to have been caused by agricultural activity. More likely, it was done using tools during the garnet setting or before burial.

Also included in the set is a gold disc pendant with a garnet in the center and eight twisted gold wire ropes radiating from the stone in a star shape. It shows minor damage to the gold wire border and filigree. The second round gold-tone pendant features beaded filigree on the ring and S-shaped scroll. Its center once contained a gemstone, but it has been lost. The gold piece in the upper left corner has been bent inwards.

Also included in the set is a gold disc pendant with a garnet in the center and eight twisted gold wire ropes radiating from the stone in a star shape. It shows minor damage to the gold wire border and filigree. The second round gold-tone pendant features beaded filigree on the ring and S-shaped scroll. Its center once contained a gemstone, but it has been lost. The gold piece in the upper left corner has been bent inwards.

The fourth pendant is the smallest pendant in the set. It is a lightweight piece made of gold sheets with a gold bar border and decorated with gold beads. The center is set with a deep red gemstone (possibly a garnet). There is a crack on the surface.

The fourth pendant is the smallest pendant in the set. It is a lightweight piece made of gold sheets with a gold bar border and decorated with gold beads. The center is set with a deep red gemstone (possibly a garnet). There is a crack on the surface.

The final piece is a domed gold boss decorated with garnet cloisonné cells. The round cell in the top center contains remnants of garnet, and only two of the five triangular cells on the sides still contain garnet. The units have gold wire borders, one is undecorated and two are beaded. This may have been the dome of a brooch, which was later transformed into a pendant. This is the first example of the ‘crown arch’ decorative style found in Lincolnshire.

The final piece is a domed gold boss decorated with garnet cloisonné cells. The round cell in the top center contains remnants of garnet, and only two of the five triangular cells on the sides still contain garnet. The units have gold wire borders, one is undecorated and two are beaded. This may have been the dome of a brooch, which was later transformed into a pendant. This is the first example of the ‘crown arch’ decorative style found in Lincolnshire.

The pendant with a large garnet inlay was part of an elaborate necklace that also included beads, spacers and smaller pendants that were found in the tombs of high-status women of the period, but this assemblage lacks other necklace elements or any other artifacts commonly found in Anglo-Saxon female tombs. There was no evidence of graves or human remains at the discovery site. A metal detector repeatedly explored the area for more than a decade but never found any other Anglo-Saxon artifacts or burial material.

Lisa Blundell, discovery liaison officer for the Lincolnshire Portable Antiquities Scheme, has been studying these assemblages and recently published a report in Oxford Journal of Archeology.

Blundell noted that the Donington collection was unlikely to be a necklace from an Anglo-Saxon woman’s grave because no beads or spacers were found to suggest they were strung together. To try to solve the mystery, Brundle turned to other explanations for why the five items were found in one group.

“One possibility is that the assemblages came from a blacksmith’s hoard,” Brendel wrote.

During the seventh century, as garnet supplies dwindled, itinerant goldsmiths may have collected some of the antique jewelry to repurpose into new accessories. How Smith collected the gems is up for debate, though, because tomb robbers have been known to target the tombs of high-status women in order to steal their precious jewels, Brendel wrote in the study.

Blundell points out that removing pendants from circulation can also be seen as a form of “ritual killing,” turning a powerful, ancient symbol of elite status into a new object that is no longer associated with these people.

But it’s also possible that one or more women simply collected their own jewelry and hid it away.

“One explanation is that these assemblages represent prized possessions of kin or social groups that were deliberately hidden during periods of instability or transition,” Brendel writes.

The combination has been declared a national treasure and acquired by the Lincoln Museum.

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

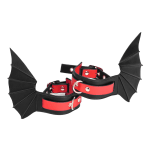

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips