16th century gallows, skeletons found in Grenoble – History

The remains of a 16th-century gallows and the skeletons of dozens of executed men have been discovered in Grenoble, France.

The site is a esplanade at the entrance to Porte de la Roche in Grenoble, built on reclaimed marshland on the banks of the Isère River. Over the centuries, the area was used for festivities, games, fairs, military camps due to its natural resources (sand, wood), although flooding was still common here until the early 19th century.

Prior to its reconstruction, INRAP archaeologists excavated it and discovered a quadrangular masonry structure containing ten burial pits inside and outside its northern wall. Most pits contain the skeletal remains of multiple individuals (between two and eight individuals), with occasional single burials. Based on the bone count, it can be determined that at least 32 people were buried, most of whom were men and a few were women, touching each other in different positions and directions.

Prior to its reconstruction, INRAP archaeologists excavated it and discovered a quadrangular masonry structure containing ten burial pits inside and outside its northern wall. Most pits contain the skeletal remains of multiple individuals (between two and eight individuals), with occasional single burials. Based on the bone count, it can be determined that at least 32 people were buried, most of whom were men and a few were women, touching each other in different positions and directions.

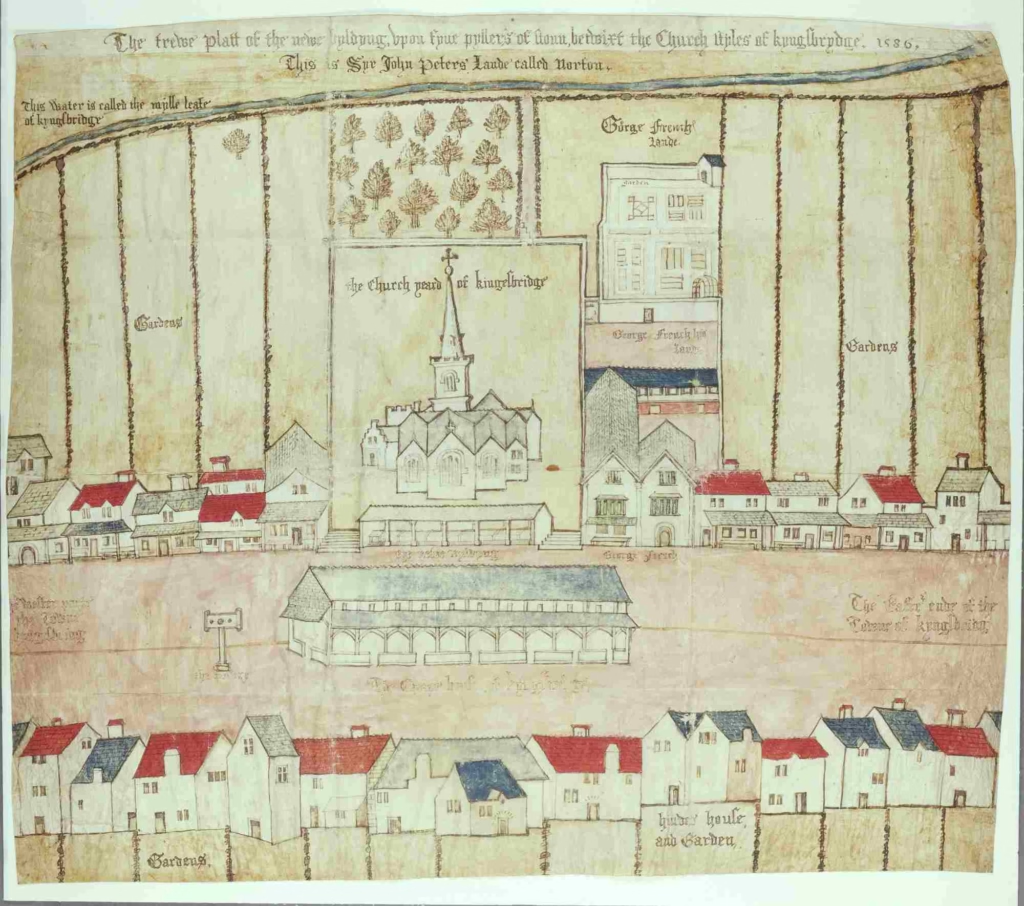

The researchers identified the structure by comparing its masonry foundations with plans for the wooden structure of the 1546 gallows at Port de la Roche in Grenoble. The measurements are exactly the same.

Construction records allow us to trace the various stages of building work between 1544 and 1547 and reconstruct the architecture of the gallows. On a masonry foundation 8.2 meters long on each side, eight stone columns stand with capitals on top, supporting a 5-meter-high wooden frame made of wooden blocks. The gallows was built on a slightly elevated site on an alluvial terrace to prevent flooding. Its east side is further protected by a drainage ditch, perhaps also to delineate its space. Its eight pillars give it remarkable originality, since this number is related to the judicial hierarchy of the kingdom: from two to six pillars in the Court of the Lords, to 16 pillars in the Royal Gallows of Montfaucon in Paris.

This is not where death row prisoners are executed. This gallows was where the bodies of executed people were displayed for varying lengths of time. The shameful exposure of the dead was part of the punishment, mostly for those found guilty of crimes against the king. In 16th century France this was usually Huguenot.

When the gallows was built, tensions between Protestants and Catholics increased, and the official government’s stance shifted sharply from tolerance of Protestants to persecution. In 1540, King François I issued the Edict of Fontainebleau, the first in a series of punitive statutes against the Huguenots. It declared Protestantism to be treason, and adherents were tortured, confiscated of property, and executed. His successor, Henry II, went a step further and issued the Edict of Chateaubriand in 1551, which called for severe punishment for all “heretics”; in 1557, the Edict of Compiègne provided for the death penalty for all convicted heretics. In 1562, persecution and religious conflicts broke out into civil war, which lasted until the end of the century.

When the gallows was built, tensions between Protestants and Catholics increased, and the official government’s stance shifted sharply from tolerance of Protestants to persecution. In 1540, King François I issued the Edict of Fontainebleau, the first in a series of punitive statutes against the Huguenots. It declared Protestantism to be treason, and adherents were tortured, confiscated of property, and executed. His successor, Henry II, went a step further and issued the Edict of Chateaubriand in 1551, which called for severe punishment for all “heretics”; in 1557, the Edict of Compiègne provided for the death penalty for all convicted heretics. In 1562, persecution and religious conflicts broke out into civil war, which lasted until the end of the century.

Exposing the bodies of those convicted of heresy or treason was part of the punishment. The humiliation of it, and the violation of deep religious beliefs about the resurrection of the body, moved the judicial verdict beyond the death penalty itself. On-site burial without proper ceremony on unconsecrated land can have eternal consequences.

Exposing the bodies of those convicted of heresy or treason was part of the punishment. The humiliation of it, and the violation of deep religious beliefs about the resurrection of the body, moved the judicial verdict beyond the death penalty itself. On-site burial without proper ceremony on unconsecrated land can have eternal consequences.

Burying a condemned man in this manner was a means of prolonging the death sentence he had been sentenced to during his lifetime: those discovered during excavations were therefore deliberately refused burial. Their bodies were sometimes dismembered and treated shamefully: buried or thrown into simple pits, sometimes layered, sometimes rearranged, without any obvious care or funereal gesture. Circumstances seemed to determine the burial method. Thus, in the large central pit, overlapping bodies were deposited first, followed by body parts and discrete skeletal remains. Elsewhere, several condemned men might be taken down at the same time and buried in the same pit.

The gallows at Port La Roche were built as the kingdom’s repression of the Reformation intensified. It probably remained in use until the early 17th century, when the policy of appeasement was implemented and Grenoble expanded under Les Digières, a former Protestant leader and the king’s new lieutenant-general in Dauphine. The discovery of this gallows, and the understanding of the practices it engendered, provides a new case study in the rapidly evolving field of research on these sites of justice—markers of jurisdiction, symbols of security, instruments of social degradation—and, more broadly, for reflection on how it might, or still might, mean a shameful death sentence.

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Construction records allow us to trace the various stages of building work between 1544 and 1547 and reconstruct the architecture of the gallows. On a masonry foundation 8.2 meters long on each side, eight stone columns stand with capitals on top, supporting a 5-meter-high wooden frame made of wooden blocks. The gallows was built on a slightly elevated site on an alluvial terrace to prevent flooding. Its east side is further protected by a drainage ditch, perhaps also to delineate its space. Its eight pillars give it remarkable originality, since this number is related to the judicial hierarchy of the kingdom: from two to six pillars in the Court of the Lords, to 16 pillars in the Royal Gallows of Montfaucon in Paris.

Construction records allow us to trace the various stages of building work between 1544 and 1547 and reconstruct the architecture of the gallows. On a masonry foundation 8.2 meters long on each side, eight stone columns stand with capitals on top, supporting a 5-meter-high wooden frame made of wooden blocks. The gallows was built on a slightly elevated site on an alluvial terrace to prevent flooding. Its east side is further protected by a drainage ditch, perhaps also to delineate its space. Its eight pillars give it remarkable originality, since this number is related to the judicial hierarchy of the kingdom: from two to six pillars in the Court of the Lords, to 16 pillars in the Royal Gallows of Montfaucon in Paris.