Wolf teeth found in ancient Venetii cremation tombs

Four wolf teeth were found in a pre-Roman cremation grave of the Veneti people in Padua, northern Italy. The deceased was almost certainly female, based on traditional female grave goods (a needle, a short knife used for weaving rather than hunting or fighting, an awl), and the four canine teeth had holes drilled in them, possibly used as pendants. Archaeologists believe that wolf teeth may have had symbolic meanings beyond ornaments and were worn as amulets.

The Eastern Necropolis was discovered in 1990, before the new student housing at the University of Padua was built. The site is huge, more than an acre in size, and archaeologists had to cover a lot of ground in a short time. More than 320 tombs, mostly cremation tombs, dating from the 9th century BC to the 3rd century AD were found in the necropolis, including the tombs of the earliest Venetians, who founded the city of Padua.

Despite the site’s continued importance, construction work continued (today it is a residence and underground parking lot), so in 1991 archaeologists had to pack up hundreds of 3,000-year-old tombs to prevent them from being knocked over by bulldozers. The Veneti buried their dead in family groups, so the tombs overlapped closely. The tombs were packed into huge blocks of earth (much larger than a typical monolithic excavation), placed in wooden boxes, some reinforced with cement, and transported to the warehouse of the Veneto Regional Archaeological Superintendency.

The first huge “block” was excavated in 1999. After a period of interruption, excavations resumed in 2007 and 2009, but then there was another longer break until 2017. Since then, the burial boxes have been excavated every year, led by archaeologists from the Ca’ Foscari University in Venice.

The first huge “block” was excavated in 1999. After a period of interruption, excavations resumed in 2007 and 2009, but then there was another longer break until 2017. Since then, the burial boxes have been excavated every year, led by archaeologists from the Ca’ Foscari University in Venice.

So far, archaeologists have discovered two types of cremation containers: wooden boxes, of which only the impressions of the corners remain, and pottery jars, huge clay jars used in ancient times as storage containers. The jars contained the ashes of the deceased and funerary objects (bronze, iron, bone and amber ornaments, ceramic jars, bowls, cups, glasses), many of which were very valuable.

So far, archaeologists have discovered two types of cremation containers: wooden boxes, of which only the impressions of the corners remain, and pottery jars, huge clay jars used in ancient times as storage containers. The jars contained the ashes of the deceased and funerary objects (bronze, iron, bone and amber ornaments, ceramic jars, bowls, cups, glasses), many of which were very valuable.

Because it had been decades since the blocks were removed, the silty clay in the dirt blocks had become very dense and hard, almost impermeable to water. Therefore, it had to be dry-excavated, with only small streams of water sprayed directly onto the soil, avoiding contact with the ceramics. There were many ceramic fragments, and the dry scraping required to excavate the boxes often caused micro-cracks to expand. To ensure that the finds remained in place for the meticulous documentation process, very thin Japanese paper was glued to the breaks with acrylic resin.

Because it had been decades since the blocks were removed, the silty clay in the dirt blocks had become very dense and hard, almost impermeable to water. Therefore, it had to be dry-excavated, with only small streams of water sprayed directly onto the soil, avoiding contact with the ceramics. There were many ceramic fragments, and the dry scraping required to excavate the boxes often caused micro-cracks to expand. To ensure that the finds remained in place for the meticulous documentation process, very thin Japanese paper was glued to the breaks with acrylic resin.

Today, Wednesday 25 September, the Excavation Lab opens to the public for a one-off event to share the extraordinary excavation process and discoveries with the public.

You can see the wolf tooth emerging from the giant clod of dirt at 2:00 and 6:10 in this Italian video. You can see a knife and an awl with a dug-out wolf tooth on top at 7:35.

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

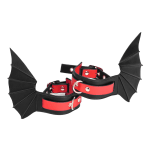

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips