Wall built to trap Spartacus found – The History Blog

Archaeologists have identified an ancient stone wall in the Dossone della Melìa, a high plateau in southern Calabria, as one of the defensive structures built by Roman general Marcus Licinius Crassus to trap Spartacus and his army of escaped slaves. The moss-covered wall is 2.7 km (1.7 miles) long and is paired with an earthwork on one side. The wall also would have originally been accompanied by a deep ditch (fossa), but that is now lost.

[University of Kentucky’s Dr. Paolo] Visona believes that Spartacus attacked the wall in his bid to break free of the trap that Crassus had constructed for him. The discovery of numerous broken iron weapons, including sword handles, large curved blades, javelin points, a spearhead, and other metal debris, indicate a battle took place at the site.

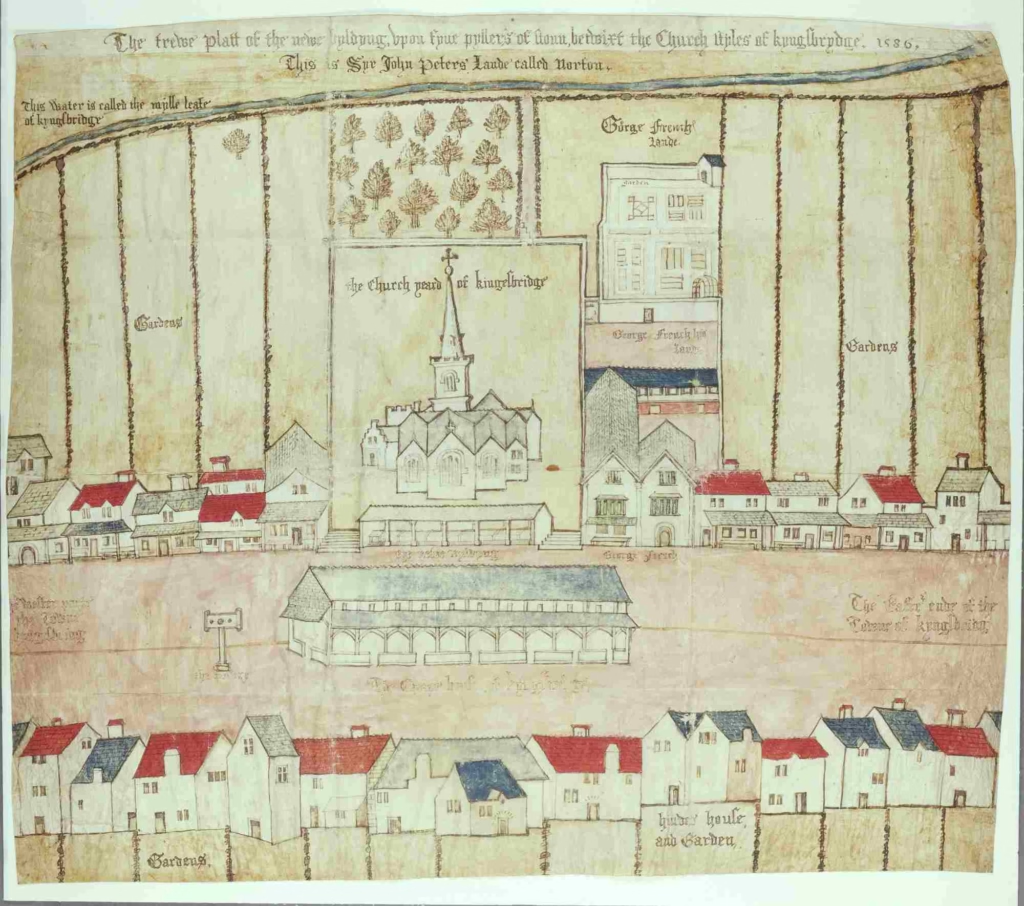

The Dossone plateau extends from the toe of Italy’s boot to the arch, from the Reggio Calabria on the Straits of Messina and the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Isthmus of Catanzaro and the Ionian Sea. It was used as the main regional pass between the eastern and western coasts of southern Italy since at least the 6th century B.C. (and continued to be used well into the 16th century). It was so strategically important to the Greek colonies in Calabria that the dominant city in the area, Locri Epizephyrii, had forts along the pass and regular patrols to protect its territory from attack by rival colonies.

Spartacus and 70 gladiators escaped imprisonment in the gladiatorial training school in Capua in 73 B.C. This tiny core expanded geometrically, drawing in enslaved rural and urban workers, shepherds, farmers, men, women and children until there were 70,000 rebels successfully raiding towns and making fools of the Roman commanders sent to quash the rebellion.

Spartacus and his co-leaders made ample use of the local knowledge in their ranks, military tactics and understanding of the terrain among them. The Social War between Rome and its former Italian allies less than 20 years earlier had seen a great deal of action in southern Italy, and there were certainly veterans of that rebellion among Spartacus’ forces. By the time Spartacus and his ragtag army made their way to Rhegium (Reggio Calabria) in 71 B.C., however, the richest man in Rome, the ruthless general Marcus Licinius Crassus, was on his tail. Crassus cut off access to the Straits of Messina so Spartacus could not flee to Sicily and he ordered construction of fortifications to block their movements and supply chains.

Hemmed in by Crassus and with news that Pompey’s legions, fresh from war in Spain, had been dispatched to crush the rebellion once and for all, Spartacus busted through the fortifications and headed east for the heel of the boot. They didn’t make it. They made a hard turn north and the final confrontation between the Spartacan army and the Roman legions of Crassus took place in 71 B.C. in Senerchia, 260 miles north of Rhegium.

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips