Shuzo Hamachi is rebuilding bonsai from pots

For someone who works with small trees, Hamacho Shuzo is unusually tall. At nearly 2 meters tall, he dwarfs the bonsai he prunes, cares for and studies every day in his Fukuoka studio. The scale is inverted: an artist of stature devoted to the discipline of miniature worlds.

The origins of bonsai can be traced back to ancient Chinese art penjingoften composed of miniature landscapes composed of a variety of elements such as rocks, water, and trees, to evoke the vast natural landscape within the pallet. When the practice reached Japan during the Heian period, its focus gradually narrowed: the landscape was condensed into a single tree, a symbol of the entire environment. Over the centuries, this transformation produced a discipline shaped by proportion, restraint, and formal balance. To depart from these conventions is to challenge the order of the craft itself.

Hamachi’s work began at that tense moment.

formal philosophy

Hamachi was born in Kamakura, a coastal city in Kanagawa Prefecture, and grew up amid the salty air and low mountains. His father settled here after graduating from the University of Tokyo, attracted by the tight-knit seaside community and laid-back life. There is a bonsai in their garden. It died a few years later, but something about it stayed with him.

Over the years, bonsai has gradually become marginalized. He sold the car and started his own business. Then, at age 36, he reconnected with a former classmate, bonsai artist Isao Tokunaga. He began experimenting with plants, and his initial curiosity soon turned into the study of balance itself—not just in trees, but in the structure that sustains them.

In Japan, bonsai remains a hierarchical world, with six-year apprenticeships and closed guilds governing who can call themselves professionals. Hamachi came in from the margins—under the tutelage of his mentor Tokunaga, but without the sanction of blood. This freedom shaped his emotions.

Traditionally, bonsai artists practice Yakakuse: Carefully select pots that harmonize with the shape, size and characteristics of your trees. Often, the pots chosen are antique ceramic vessels, which are as valuable as the tree itself. Hamachi does things differently. In his studio, trees are inhabited by gleaming stainless steel containers that catch light like mirrors. The effect is precise but not icy, the organic vibrancy of the trees combined with the designed transparency of the containers. “When these two emotions – natural and industrial – meet, they balance each other out,” he said. “It feels very appropriate for our times. A touch of warmth in the concrete jungle.”

The decision is both practical and aesthetic: “Some trees grow horizontally, almost lying down,” he explains. “A lightweight ceramic pot will just tip over. Urban materials like metal, steel and acrylic allow you to control quality.”

reinvent tradition

For Hamacho, this raises a larger question: what qualifies as a bonsai. “I call it rebuilding,” he said. “It’s not just pruning branches, it’s designing pots, fixtures and the whole environment. If someone wants to cut a baseball in half and grow a bonsai in it, that’s totally fine.”

For purists, this freedom once bordered on heresy. Bonsai has long been regarded as a high-level craft, and its methods are treated with almost religious care. Hamachi’s openness redefines it as a democratic and playful art form—one that is applicable to everyday life and not just for display. “To me, rebuilding means tearing down that wall,” he said. “Tradition doesn’t need protection behind glass; it needs participation.”

This is the core of his philosophy: not to reject tradition but to reshape its conditions of existence. “Even a rotten tree, even an unfinished tree can be beautiful,” he said. “Just because something is overlooked doesn’t mean it’s not worth seeing.”

Two of his works, Creation and Ichimori, make this idea evident. In these works, he threaded ephemeral cut flowers through a century-old tree, allowing one element to burn and disappear in a matter of days while another endures for generations. Friction is the point: mayflies and longevity, flowers and bark.

“Bonsai grows over time,” he said. “Short-lived works are dazzling because they are fleeting; long-lasting works have weight and dignity. Together they carry two meanings – finite and continuous. This mixture of time scales is part of my signature style.”

For Hamachi, bonsai is a way of thinking about time and the responsibilities it demands. Some of his trees are hundreds of years old and have passed through many hands before him. “They’re going to outlive me,” he said. “In that timeline, I was just a baby. Every tree has its own history – it has been through, struggled, broken, but still pursues the light.”

Landscape: Living Gallery

The idea of rebuilding transcended his trees. In Fukuoka City’s Hakata district, Hamachi runs Scapes, a studio that functions as a gallery, studio, and administrator’s bench. People from all generations have come to buy bonsai, learn how to keep them alive, or leave their trees in his care while traveling. Others just stopped to sit and drink tea and chat. “I wanted a place that anyone could walk into,” he said.

This openness pervades his collaborations. Hamachi collaborates with metalworkers, architects and ceramicists who bring new materials and emotions to his creations. One of his current projects is a collaboration with the famous Imari kiln Hataman Touen. Together they are developing new bonsai pots that reinterpret Nabeshima porcelain, an Edo period porcelain style known for its geometric patterns and restrained color palette.

He is also involved in a more unusual collaboration with researchers at Kyushu University, who are analyzing the mathematical rhythms of his works: the proportions between trunks and branches, the spacing of negative voids, and the asymmetries that the human eye still perceives as balanced. This approach treats bonsai as a perceptual architecture—a form whose harmony can be described, studied, and measured, rather than just intuitively understood.

Hamachi himself is interested in digital preservation – the idea of using blockchain or similar systems to record bonsai. “Not for the money,” he clarified, “but for the history.” A living database, he suggested, could document each tree’s lineage—its owners, exhibitions, transformations—preserving knowledge that is often lost in private collections. “Some of these trees have been there for centuries,” he said. “But their stories are lost along with their owners. That’s the real loss.”

Taken together, these efforts describe his ambition. Hamachi is more than just refined bonsai. He is rebuilding an ecosystem around it—how to show, how to teach, how to measure, how to remember. “The craftsmanship, the environment, even where people encounter bonsai—all of these can evolve,” he said. “I want it to feel as natural as saying, ‘I like to draw.’ Let people touch it, enjoy it, let it become a part of their lives.” “

More information

Follow Hamachi on Instagram.

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

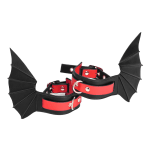

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips