Revealing the “Three Major Villains” of Japan’s Warring States Period

The Japanese do like to divide things into three groups. A lot of the time, they get it right, like the three most beautiful places in Japan, which are truly the cutest places you can visit all over the country, both Old and new versions. But there are also the three great villains of the Sengoku period: samurai active in a period of near-constant civil war who were notorious for their alleged cruelty. No one is saying these guys are angels, but what exactly makes professional warriors evil, especially in a time when everyone is killing each other?

Matsunaga Hide: Teapot Villain

Matsunaga Show(1508–1577) was a close friend and retainer of Miyoshi Nagayoshi, a lord of several Kansai provinces who had control over the Kyoto imperial family and the shogunate. Hisahide loyally followed his master’s orders and conquered Yamato Kingdom (now Nara Prefecture), consolidating his power base. But when Nagayoshi’s brother and son died, the warlord’s adopted son Miyoshi Yoshitsugu was named heir despite being too young to rule, severely weakening the clan’s position.

Later, rumors began to spread about how Hisahide orchestrated all the deaths and successions, but not everyone believed it, including Yoshitsugi. In fact, he personally requested Hisahide’s help in assassinating the Japanese puppet military ruler Ashikaga Yoshiteru who was trying to consolidate power and threaten the Miyoshi clan.

Hisahide and Yoshitsugu eventually became enemies as the former fought for control of Yamato, one of which ended with the burning of the Todaiji Daibutsu Hall, which Hisahide allegedly ordered. However, as with the assassinations of the Miyoshi family, there is absolutely no historical evidence that he wanted to destroy one of the country’s most important and sacred Buddhist places of worship.

Some sources claim it was an accident. Others put the blame on a lone soldier on Miyoshi’s side. So why is Jiuxiu remembered now? This may be related to his conflict with Oda Nobunaga. Hisahide sometimes allied with Nobunaga and sometimes fought against him (as was the case during the Warring States Period).

Nobunaga finally had enough. He attacks Kuhide and demands his head. Legend has it that Nobunaga also wanted his antique teapot. Avid collector of such items. But in a final act of defiance, Kuhide allegedly smashed the pot before committing seppuku.

The list of the Three Great Villains was most likely intended to identify the evil rivals of the three great unifiers of the period: Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu. Hisahide naturally became Nobunaga’s nemesis, even if the evidence for his evil deeds—such as burning down Japan’s spiritual center—had to be completely fabricated.

Saito Dozo: The Viper of Mino

Saito Dozo(1494–1556), the governor of Mino Country, is another big villain associated with Nobunaga. His daughter Nohime married Nobunaga, but the couple had no children, not quite. picture of happy marriage. However, this is not the reason why Dosan is on the list.

His ruthless tactics earned him the nickname “The Minnow Viper,” but what about the whole villain tag? This actually had more to do with his humble beginnings, as he started life as a monk and later became an oil seller. A very successful man, but a career of going door to door filling people’s buckets and pots with oil didn’t win him a lot of respect.

Michizan then requested to become a vassal (i.e. samurai) of Nagai Nagahiro, who served the Toki clan, ruler of the Mino Kingdom. He quickly rose through the ranks and gained the trust of Toki Yori-inari, helping him eliminate any family members who stood in the way of Yori-inari one day taking over the Toki clan. Along the way, he also planned Changhong’s death.

When the Toki became friendly and unstable, Dozo attacked and poisoned Rainari’s brother. After raiding Yori Cheng’s residence, he exiled his former master and became the lord of Mino through the so-called “Mino”. Yueguocheng (“The lows beat the highs”). Still, this was common in his day, so why single out this man?

Well, while their lives never really crossed paths, Dozo’s inclusion on the list was likely due to Toyotomi Hideyoshi, his evil counterpart. Like Shimazo, Hideyoshi was a commoner who rose to a position of power through strong will and cunning.

Many high-ranking samurai hated bowing to former peasants. But Hideyoshi was a respected and powerful figure, so it was difficult to criticize him directly. So history – which was and is written primarily by the rich and powerful – came up with a solution: vilify another warrior who broke the unspoken rule against ambition from humble beginnings.

Naoe Ukita: A victim of narrative convenience?

Naoe Ukita (1529–1582) was born into a simple samurai family in modern-day Okayama Prefecture, and lived a life befitting the protagonist of a historical drama. After his grandfather was assassinated by the Shimamura clan, he barely escaped death and became the head of his family at the age of seven, before joining the service of the local lord Urakami Munekage.

He is ordered to marry the daughter of a neighboring lord and soon discovers that his father-in-law is planning to attack Munekage with the Shimamura clan. Assuring his master that he would have no problem killing his father-in-law if he could avenge his grandfather, Naoe got the green light to clean house, so he ambushed his wife’s father in a teahouse and later on the battlefield.

Years later, most likely driven by ambition, Naoe declared war on his master, eventually overthrowing Munekage and taking over Bizen Province. Before his death at Okayama Castle, he promoted the development of Okayama by improving road transportation and helping attract more merchants to his territory. His actions of changing allegiances and killing his father-in-law are often cited as reasons why he is considered a villain, but these things were so common during the Sengoku period that this simply cannot be the entire story.

We go back to history again to find the evil counterpart to the heroes of that period by focusing on superficial similarities and twisting the facts, because things make more sense when they are symmetrical and the bad guys and good guys are clearly defined. Naoe was a very methodical and patient warrior, qualities that would later be associated with Tokugawa Ieyasu. Although the two never came into conflict, Naoe’s son Hideie did fight Ieyasu, who completed the conquest of Japan. This is enough to symbolically connect the two.

Ultimately, these three so-called villains serve less as objective biographies of villains than as a lesson in how finding narrative meaning in a messy history can lead to gross distortions of the truth.

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

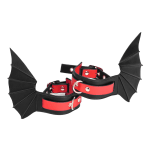

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips