Mileage May Vary: Marathon Sense of Belonging

This post may contain affiliate links, which means we receive a small commission on any sales. This committee helps Feminist Book Club pay our contributors, so thank you for supporting small independent press!

If I could tell my 15-year-old self—who barely managed a mile in gym class—that I would one day run a marathon, she would probably view it as cruel punishment. Like many women, I started running in my 30s. I ran my first marathon at age 34 and ran my fastest time to date at age 37. I didn’t feel like I was past my physical prime, and distance running showed me that I could surprise myself time and time again with how far and how far I could run. Come on I can leave.

My companion is very nice. Marathons have proven to be inclusive in ways I never expected. Many of my running heroes competed in their career races in their 30s or even later. Des Linden was 34 when she won the 2018 Boston Marathon, making her the first American woman to win the event in 33 years. Shalane Flanagan was 36 when she won the New York City Marathon in 2017. Kiera D’Amato set the American half marathon record in 2023 at age 39. In 2023, Courtney Dauwalter, considered by many to be the greatest ultramarathoner of all time, became the first person to win three major ultra events: the Western States 100, the Hardrock 100, and the Ultra- Trail du Mont Blanc in the same year, 38 years old.

Many of these women continue to dominate and advance well into their 40s. This is in stark contrast to the ageism prevalent in many competitive sports. This is not just an elite trend. The average age of female marathon runners is 37.91 years old. More and more older runners are taking part in marathons. Taking the New York City Marathon as an example, in 2013, 20.6% of runners were over 50 years old; by 2023, this proportion will increase to 24.4%.

There are still barriers to entry into distance running, including physical and financial limitations. There are also growing efforts being made by various organizations, individuals, brands and running clubs to address racial disparities. Despite these areas for improvement, Marathon Day in New York felt warm, supportive, and inclusive.

There are many different types of people showing up on game day with different goals and abilities. Most of the people you see on the course are simply racing against themselves—trying to break a personal record, or happily celebrating completing a race. Crowds gathered in the streets of New York cheering them for hours. Spectators don’t just encourage runners. They provide tissues, Band-Aids, snacks and sunscreen. They stayed outside after dark with their children, dogs and homemade signs and costumes. NYRR, the organization responsible for the marathon, is dedicated to celebrating the marathon’s final finishers, who arrive after the sun sets. Achilles International helps people with disabilities cross the finish line. Every marathon day I am moved to tears by the runners, walkers, wheelchair athletes and the people who cheer them on.

I no longer know if I couldn’t run a mile in high school or if I just didn’t want to. I was a rebellious teenager. I didn’t follow instructions or turn in assignments on time. My attendance was low. So of course I ignored the PE teacher’s instructions. But I was also convinced that I was terribly unathletic. Aside from a few weeks playing softball in elementary school (my mother remembers another parent leaning on her and saying, “Sam Paul just can’t focus”), I never played any organized sports.

After school I worked at a dry cleaners. In senior grade, my gym teacher from a few years ago came in to iron a shirt. “Sam Paul,” he said with a smile, “remember that time you caught the ball?”

I remember it very clearly. This really only happens once, during a kicking game. The ball came straight towards my face. I raised my arm in self-defense and it landed directly in my outstretched hand.

By the age of 15, I had also become a pack-a-day smoker. After school, I went to a convenience store called Verona Variety, where the owner would sell me cigarettes. My taxes as a minor were putting up with his vulgar remarks: “Newport Lighthouse, stay (redacted) tight,” he told me with a wink.

Smoking stayed with me into adulthood, even as I started to become more physically active. I started riding my bike and took delivery jobs on my bike. Still, I smoked regularly. As I rode through the city, I smoked cigarettes all day long. At home, I pause the TV and go outside when I’m nervous. I would rush to the door after movies and flights, and if I was worried about not having anything in the morning, even in a snowstorm, I would go out and buy a pack in the middle of the night.

Part of the reason I started running was to quit smoking. I signed up for my first five-mile race so that it loomed on my calendar – it was probably going to be bad anyway, but it would be even worse if I fell into the habit again .

After get off work, I would run a few miles around the park in the dark. I couldn’t run very far at first, so I ran a few laps without walking. I listened to an app called “Zombies Run!” (Written primarily by Naomi Alderman, author strength) and imagine yourself being chased. I ran a mile, two miles, five miles non-stop, across bridges and into Manhattan and Queens. Competitions come and go. I don’t hate it, and I still don’t smoke. A friend and I signed up for a half marathon. We randomly selected a training plan and printed out a random grid that I googled, crossing out the days that came and went. The miles add up and that’s it.

It turns out I love training. I couldn’t believe it when my legs first walked a mile, then five, then ten. Running has become a habit, a force that supports myself and me. At the end of my first half marathon in 2019, a 13.1-mile run from Brooklyn to car-free Times Square and finally to Central Park, I felt a rush for my legs, my lungs, and the city. Gratitude, in conversation with myself in less than two hours. I knew then that once I figured out how to run, I would run a full marathon.

I would never win a medal that wasn’t a participation award, but participation is a gift in itself. The marathon itself is a 26.2-mile celebration. I hope more and more people will get involved and encourage people of all ages, abilities, races and backgrounds to get to the starting line. The marathon isn’t for everyone, but it’s for a lot more people than I thought. Sometimes I’m still surprised that they fit me.

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

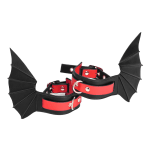

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips