Massive burials discovered in Leicester Cathedral in the 12th century——

One of the largest mass graves ever discovered in Britain was unearthed next to Leicester Cathedral. The pit contains the skeletal remains of 123 men, women and children, which were dumped into a narrow vertical shaft in the early 12th century.

“Their bones show no signs of violence, which leaves us with two causes of death: starvation or plague,” said Matthew Morris, project officer for the Archaeological Service at the University of Leicester. “At the moment, the latter is our main focus Assumption.”

Excavations by Morris and his colleagues revealed that the bodies were lowered into the shaft on three separate occasions in rapid succession. He said: “It looks like a continuous carload of corpses was transported to the shaft and then fell in. In a very short period of time, carloads were piled on top of each other.” “Judging from the number, the number of people inside was about About 5% of the town’s population.” […]

Morris said that the “Anglo-Saxon Chronicle” repeatedly mentions that from the mid-10th century to the mid-12th century, severe plagues and fevers, serious deaths, and tragic deaths due to hunger and famine occurred in England. “This mass burial fits this time frame and provides physical evidence of what was happening across the country at that time.”

The discovery of the remains of King Richard III in a Leicester car park in 2012 led to a dramatic transformation of Leicester Cathedral’s identity as a place of worship, pilgrimage and tourist attraction. In 2015, his remains were reburied in a purpose-built tomb at Leicester Cathedral, leading to a tenfold increase in church attendance.

In January 2022, the cathedral closed for two years while the building was repaired and restored to ensure its long-term stability, the first phase of an ambitious £15 million refurbishment project. At the same time, the old Song School, located in the garden green at the east end of the cathedral, was demolished to make way for the new Heritage and Learning Center (HLC). Service resumes on November 26, 2023, with

In January 2022, the cathedral closed for two years while the building was repaired and restored to ensure its long-term stability, the first phase of an ambitious £15 million refurbishment project. At the same time, the old Song School, located in the garden green at the east end of the cathedral, was demolished to make way for the new Heritage and Learning Center (HLC). Service resumes on November 26, 2023, with

The University of Leicester Archaeological Service (ULAS) was involved in the exploration of the HLC construction site.

The Cathedral Gardens are a peaceful green space that has been developed over the past 80 years from what was once the old churchyard (no new cemeteries were opened in 1856). In the centuries before its closure, the cemetery was more than just a burial ground. Like many cemeteries, it was a park-like gathering place for residents of densely populated urban centers, and archival and archaeological evidence suggests that the building dates back to the 12th century, and that the church rented residences to tenants from the 15th to 18th centuries.

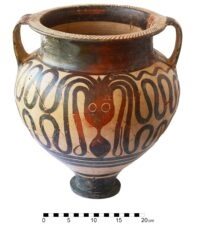

What is now Leicester Cathedral was originally the parish church of St Martin’s. The first mention of its name in historical records is in 1220, but historians believe that an earlier version of St Martin’s Church dates from before the Norman Conquest. In excavations at the HLC site, archaeologists hope to find evidence of the earliest churches, as well as the remains of the ancient Roman settlement Ratae Corieltavorum, much of which lies beneath Leicester’s historic center and is therefore inaccessible to archaeologists.

Excavation work will end in March 2023. Excavating for 10 months in a relatively small pit measuring 43 by 49 feet by 20 feet deep, the team unearthed 19,754 artifacts and 1,237 skeletons spanning 15,000 years of history. The tombs date from the 11th to 19th centuries, the entire period in which St. Martin’s churchyard was in use.

“This is an 850-year continuous burial sequence from a single population in one place, which is not very common,” Morris added. “It yields a wealth of archaeological results.”

After documenting and evaluating archaeological material collected from the site, the ULAS team analyzed the skeletal remains. The bones were subjected to osteological analysis, radiocarbon dating, DNA and stable isotope analysis. Dating confirms that St. Martin’s College was founded in late Saxon times (a penny found in this layer dates to AD 880-973), and while much of the site is Roman-era garden space, its northwest One quarter has a cellar. The building has a cellar with stone walls and a concrete floor. The base of an altar stone was found there, suggesting it may have been a private cult ritual space.

After documenting and evaluating archaeological material collected from the site, the ULAS team analyzed the skeletal remains. The bones were subjected to osteological analysis, radiocarbon dating, DNA and stable isotope analysis. Dating confirms that St. Martin’s College was founded in late Saxon times (a penny found in this layer dates to AD 880-973), and while much of the site is Roman-era garden space, its northwest One quarter has a cellar. The building has a cellar with stone walls and a concrete floor. The base of an altar stone was found there, suggesting it may have been a private cult ritual space.

Analysis of bones from the burials showed they were older than previously thought. Because there were so many bodies in the shaft, archaeologists first suspected they were victims of the Black Death, which swept across Europe and killed a third of the population. This would be the first archaeological evidence of the Black Death in Leicester. Instead, radiocarbon dating showed the deceased had been thrown into the pit 150 years ago.

To identify possible causes of the mass deaths, the ULAS team has sent bone samples to the Francis Crick Institute in London for DNA analysis to identify the pathogen.

“This is obviously a devastating outbreak that resonates with recent events, particularly the COVID-19 pandemic,” Morris said. “But it’s also important to note that there is still some form of citizen control. There are still people. Driving around collecting bodies, what we saw from studying the bodies in the pit does not suggest it was created in a panic.”

He added: “There was also no evidence of any clothing on the bodies – no belt buckles, no brooches, nothing to suggest that the men were lying in the street before they were collected and dumped.

“Indeed, there were signs that their limbs were still together, suggesting they were wrapped in shrouds. Therefore, their families were able to prepare the bodies for burial before central authority personnel collected them for burial.”

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips