Deciphering a Roman wooden writing tablet from Belgium –

Traces of writing on the wooden remains of a Roman wax tablet found in Tongeren, Belgium, have been deciphered. They reveal new information about the cities on the northern edge of the Roman Empire, including the people who lived there, the rarely recorded presence of high-ranking officials in the northern provinces, and some proper names that had never been discovered before.

The tablets were deciphered by Professor Dr. Markus Scholz, an archaeologist and inscription expert at Goethe University in Frankfurt. He made headlines in December 2024 when he and his team deciphered a 3rd-century Frankfurt silver inscription, revealing that tightly rolled pieces of silver were the earliest archaeological evidence of Christianity north of the Alps.

Tongeren is considered the oldest city in Belgium and was founded around 10 BC as a military fortress for Atuatuca Tungrorum. It was located between the Scheldt and Meuse rivers in what is now eastern Belgium. As often happened at Roman army bases, local civilians (in this case the Tongrians) settled there for commercial opportunities. After the departure of the legions during the reign of Tiberius (14-37 AD), the city continued to grow and prosper.

Atututukagngrorum did suffer at least three fires, one in the first century AD, one in the second century and one in the third century AD, but by the fourth century it had begun to decline under the pressure of Germanic invaders from across the Rhine. Thicker defensive walls were built at the time, but they were no match for the Huns, who destroyed much of the ancient city in 451 AD

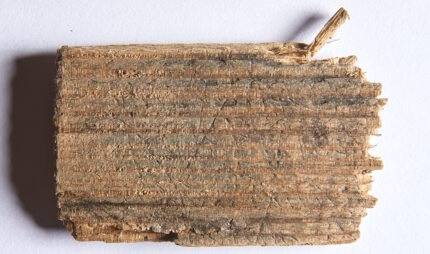

In the 1930s, archaeologists first discovered wooden fragments in Roman strata that proved to be the remains of writing tablets. The wood is the base and frame of the tablet. It is coated with a thin layer of wax and then written on with a sharp stylus. By the time the stele was discovered, the wax had long since disappeared, and archaeologists in the 1930s believed that no trace of writing remained on the wood.

The wood fragments were stored away and forgotten until they were rediscovered in 2020 by Else Hartoch, director of the Museum of Gallo-Romans in Tongeren. Hartock invited Professor Scholz to investigate possible inscriptions as a pandemic project. This is a major challenge. The wood is grained, dry and cracked, so it’s hard to tell if it’s a line of writing or just part of the wood. Some of the slates were reused, the old wax stripped off and new layers applied, so the traces of writing left on the wood are palimpsests, layers of writing layered on top of each other.

After a lot of hard work and with the help of imaging technology, Scholz and Professor Dr. Jürgen Blänsdorf, emeritus professor at the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, succeeded in deciphering the tablets.

The 85 surviving fragments come from two different archaeological contexts. A collection of stone slabs that appear to have been deliberately destroyed and discarded were found in a well near the Forum and other public buildings. Throwing them down a well will most likely ensure that the information they contain can no longer be read – perhaps an ancient form of data protection. As Scholz and Brandsdorf discovered, many of these texts are contracts or official records. “When drafting contracts, scribes deliberately applied strong pressure to imprint the words deeply into the wood,” Scholz explains. The second set of debris came from a muddy depression that was apparently filled with worn out pills and other trash that aided drainage. Here, the researchers also discovered different types of texts, including administrative copies and student writing exercises (often the end use of the tablets that had been reused), as well as a draft inscription for a future statue of Emperor Caracalla, which dates to 207 AD. […]

Only about half of the 85 fragments retain identifiable traces of writing. Even so, the deciphered letters, words, and names yielded important historical insights. There is evidence that Roman provinces also held high political offices. The tablets mention decemvirs (high magistrates) as well as lictores (acolytes of major state or municipal officials) – roles that had previously been rarely documented in the northern provinces of the Roman Empire. The texts also shed light on the people who lived in the area. Some people appear to have settled in Tongeren after serving in the Roman army, including veterans of the Rhine fleet. The names recorded on the clay tablets indicate a very diverse population, including Celtic, Roman and Germanic ancestry. Some of these names were previously unknown from other sources.

The full results of the investigation have been published in a well-illustrated academic book detailing the study and findings. In exciting news for anyone who can now go down the 424-page rabbit hole, the full monograph is also open access and can be downloaded as a pdf or read online here.

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips