Bernini’s Baldacino shines again in St. Peter’s Basilica – The

The baldachin above the high altar of St. Peter’s Basilica was designed by the Baroque architect and sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini. After nine months of restoration, it glowed with its original shining gilded glory. Funded by the Knights of Columbus at a cost of €700,000 ($770,000), this is the first comprehensive restoration of the massive 10-story building in 260 years. It was only dusted and surface cleaned (by someone hanging from a rope).

Pope Urban VIII Barberini (1623-1644) commissioned Bernini in 1624 to build a magnificent canopy (the canopy under which the Eucharist is celebrated) for the new cathedral. The canopy was completed in 1633, but work continued for two more years after that.

Over 95 feet tall and weighing 63 tons, the Baldacchino is located at the intersection of the apse and nave of St. Peter’s Basilica, serving as the centerpiece beneath the church’s dome and above St. Peter’s tomb. The four spiral columns are 37 feet tall and weigh approximately 9 tons. Bernini divided them into three parts and partially filled them with concrete for stability. They used so much bronze to make it that they snatched some from the bronze latticework of the Pantheon’s portico and even dismantled the ribs of the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, which they then recycled with lead.

Over 95 feet tall and weighing 63 tons, the Baldacchino is located at the intersection of the apse and nave of St. Peter’s Basilica, serving as the centerpiece beneath the church’s dome and above St. Peter’s tomb. The four spiral columns are 37 feet tall and weigh approximately 9 tons. Bernini divided them into three parts and partially filled them with concrete for stability. They used so much bronze to make it that they snatched some from the bronze latticework of the Pantheon’s portico and even dismantled the ribs of the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, which they then recycled with lead.

The columns spiral up from marble and alabaster bases engraved with the papal coat of arms and the bee of Barberini’s coat of arms. Their lower third is fluted, and the upper two-thirds are wrapped with gilded laurel branches. They are topped by Corinthian capitals.

The spiral-shaped columns were called “Solomon’s Columns” because it was erroneously believed that Constantine gave a set of 12 twisted marble columns to Old St. Reused on the high altar. in Jerusalem. Of course, by the time Constantine showed up, Solomon’s Temple had been destroyed for 900 years, and the Second Temple had been destroyed for about 250 years. They were most likely taken from Greek temples as they were made of Greek marble.

The spiral-shaped columns were called “Solomon’s Columns” because it was erroneously believed that Constantine gave a set of 12 twisted marble columns to Old St. Reused on the high altar. in Jerusalem. Of course, by the time Constantine showed up, Solomon’s Temple had been destroyed for 900 years, and the Second Temple had been destroyed for about 250 years. They were most likely taken from Greek temples as they were made of Greek marble.

When the old St. Peter’s Basilica was demolished in 1505, the original eight columns were reused in the new cathedral, and can be seen on the four walls opposite the baldachin beneath the four evangelical medallions that connect the church’s massive square piers. See these columns to the dome. Bernini used them as an example when designing his massive bronze columns. Today, they ignore their replacements, who appear incongruously small by comparison.

More bees, cherubs, dolphins, bay leaves and weird faces adorn the columns and canopy. A fringed panel along the top edge that looks like a fabric banner hanging from a parade canopy inspired this non-movable version. The interior ceiling of the canopy is made of gilded wood and is decorated with doves of the Holy Spirit framed by acanthus leaves, harpies and bees. Angels stand at the four corners of the canopy, and two cupids hold the papal miter above the keys of St. Peter.

More bees, cherubs, dolphins, bay leaves and weird faces adorn the columns and canopy. A fringed panel along the top edge that looks like a fabric banner hanging from a parade canopy inspired this non-movable version. The interior ceiling of the canopy is made of gilded wood and is decorated with doves of the Holy Spirit framed by acanthus leaves, harpies and bees. Angels stand at the four corners of the canopy, and two cupids hold the papal miter above the keys of St. Peter.

The size and complexity of materials used to build the structure (marble, bronze, iron, various types of wood, various types of gilding, paint) make it a huge conservation challenge. Even the simplest of cleaning tasks is far from simple, and less than 130 years after it was built, Baldacchino needed a thorough treatment. Documents in the cathedral’s historical archives record that 60 people worked every day for three months cleaning, strengthening, repairing and replacing damaged or worn parts of the baldachin.

The size and complexity of materials used to build the structure (marble, bronze, iron, various types of wood, various types of gilding, paint) make it a huge conservation challenge. Even the simplest of cleaning tasks is far from simple, and less than 130 years after it was built, Baldacchino needed a thorough treatment. Documents in the cathedral’s historical archives record that 60 people worked every day for three months cleaning, strengthening, repairing and replacing damaged or worn parts of the baldachin.

The latest restoration project was announced in January this year. The entire 10-story building was covered in scaffolding as restorers began cleaning away centuries of dirt, contaminants and dust that had clung to the gilded surfaces due to centuries of human condensation and temperature fluctuations from hundreds of thousands of breaths. Bronze indoors will naturally turn a mahogany color rather than the green seen in bronze exposed outdoors, but Baldacchino’s bronze is almost black. Oils, waxes, and resins used in previous restorations can also darken the surface. Cleaning and conditioning restores its warm brown color and restores the gilding to its high luster. The restored Baldacchino was unveiled to the public and row after row of bishops on October 27 at the Synod’s closing Mass.

Also on display is the Chair of St. Peter, a wooden throne that according to tradition belonged to the apostle Peter but was actually a medieval throne given to Pope John VIII by Charlemagne’s grandson Charles the Bald at Charlemagne’s coronation . Christmas 875. The oldest parts of it date to the sixth century, so Peter had absolutely no involvement. Additionally, it is decorated with ivory panels depicting scenes of Hercules’ labors.

Also on display is the Chair of St. Peter, a wooden throne that according to tradition belonged to the apostle Peter but was actually a medieval throne given to Pope John VIII by Charlemagne’s grandson Charles the Bald at Charlemagne’s coronation . Christmas 875. The oldest parts of it date to the sixth century, so Peter had absolutely no involvement. Additionally, it is decorated with ivory panels depicting scenes of Hercules’ labors.

Usually the chair itself is not visible. It is encased in another huge gilded bronze reliquary by Bernini, which hovers above the altar where St. Ambrose, St. Augustine, St. John Chrysostom, and St. Athelus Four huge statues of Nashu stand at its corners. The Bernini reliquary is also currently undergoing restoration, so the chair is on display for the first time since 1867. It will remain on display in front of the main altar until December 8.

This video from the Knights of Columbus delves into the restoration of the Baldacca and captures a unique perspective on the process.

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

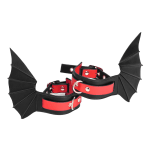

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips