An unforgettable documentary about the ‘evaporated people’ in Japan

It is reported that between 70,000 and 90,000 people are missing in Japan every year. While most people, including juvenile runaways and older people with dementia, some people cannot disappear after exercising their disappearance. They are called Johatsu, from the Japanese word “evaporated” – “evaporated man”, hoping that it will never be discovered.

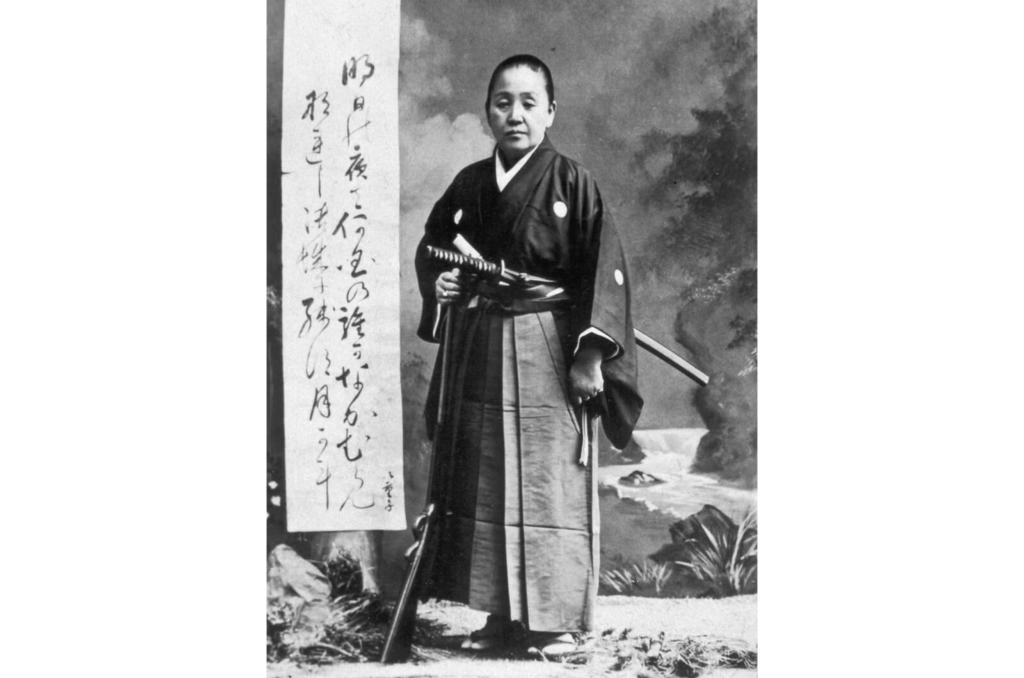

The term “Johatsu” was first used in the 1960s. After Shohei imamura’s pseudo-documentary film was released, it exploded into public consciousness in 1967. A man disappeared (Japanese title: Ningen Johatsu), records the sudden disappearance of Nigata salesman. In the 1970s, the term was often used in the media to describe people seeking to escape difficulties in daily life: for example, workplace stress or unpleasant marriages.

This phenomenon became more common after the Japanese economic bubble broke out in the 1990s and more people were in debt. In 1994, Masanori Kashimura published a book titled Complete manual for missing Provide advice on how to start a new life from scratch. Several companies have also emerged during this period to help people move cautiously.

Some people decide to disappear for many reasons: some escaped from sharks, others escaped from abusive relationships, stalkers or oppressive employers; others escaped from the shame of a failed business or a bad reputation. In their documentary johatsu: Turn into thin airGerman film producer Andreas Hartmann and Japanese director Arata Mori explore the turmoil faced by these evaporated people, and the suffering of those who left behind, and the suffering of those who left behind, and released in November 2024.

“Moving at night”

The professional business that helps people disappear is called Yonigeya, and the movie translates as “Night Walker”. Their clients are often desperate. For some, exposure to Yonigeya feels like the only alternative to suicide.

One of the main themes of the documentary is Saita, the founder of Yonigeya TSC, one of Japan’s most famous night walkers. (She prefers the last name for safety reasons.) Saita is also Johatsu – on its website, the company sees itself as “the only private organization run by experienced domestic violence and victims of stalking.”

A typical transaction starts with a phone call, discussing the details of the case. Then, a face-to-face meeting (if you can) is usually held at the client’s home to better understand where the person wants to escape. Once agreement is agreed, preparations will begin to transfer clients to secret locations.

The final step in the process is where the film begins: In the opening scene, we see Saita and an employee in the car, waiting for an abusive person to escape from his home. A few minutes later, the client, his face pixelated, rushed into the vehicle and the three of them quickly left. When his partner went to take a shower, he managed to leave.

Cautiously missing

During the pre-production process, Mori and Hartmann contacted the move for several nights. They decided to focus on Yonigeya TSC for two reasons: They felt that Saita was the most collaborative, and her story was the most compelling.

In addition to Saita, the film introduces several Johnson to the audience, including one of her staff, Sugimoto. Shameful for his failure in his business, he told his son that he was on a three-day trip to work but never returned and left his wife to take care of the children. Another theme of the documentary, Kanda, was expelled from the ground about forty years ago, because he owed Yakuza.

There is also an unnamed couple living in a spare room at a love hotel in the middle of nowhere. They often fled their home after being threatened by their boss. The harassment is very intense. According to the two, any mistakes they made were fined, meaning they were never sure how much they were to pay.

“Just listening to their stories is painful,” Morrie said. “You heard about so-called black companies in Japan, but usually in a big company, and people are overworked. I’ve never heard of something like this, where workers are forced to pay. It obviously makes them psychologically messed up, and even now, they can’t leave the love hotel, so they’re like they’re in prison.”

Mori and Hartmann are not only focused on those who disappear, but the documentary follows a tortured mother to find her son. Since Japanese police will not be able to investigate unless there is a crime or accident proof, her only option is to hire a private detective. However, Japan’s strict privacy laws make it an extremely difficult task. ATM transactions cannot be tracked, access to telephone records is prohibited, and security camera recordings are not open to the public.

“It’s not just someone who escapes life,” Hartman said. “So we think it’s important to show the other side of Johnson Pine’s world from the perspective of a mother who was abandoned and desperately tried to find the answer. She didn’t decide to leave, but she had to deal with it.”

Explain a taboo topic

Hartman decides to start working John After completing another documentary, A free manabout a Japanese who chooses to be homeless. Both deal with similar topics: the pressures of strictly performance-oriented societies, and the distance some will escape them.

Mori was born in Japan but lived abroad for nearly two decades and once she heard about the project, she was attracted to it. Research on this film was an eye-opening experience for him. “Of course, I know the word johatsu, but I don’t realize the universality of Japanese society,” he said. “It’s often seen as a taboo topic – but when I talk about this project with friends of close friends, many people say they know a missing person.”

Although the documentary has been widely welcomed at festivals around the world, the original version of the film will not be released in Japan. This is the promise of the two directors to the protagonist of the film. One alternative version is the alternative version that uses DeepFake technology to mask participants’ identities, premiering at the 20th Osaka Asian Film Festival.

For more information on the documentary, visit Mori’s website and Hartmann’s website.

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

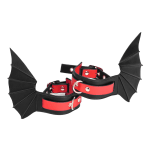

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips