Hiking Guide to the Japanese Alps

The first sound is always the same. Before the sun reaches the ridgeline and before hikers start tightening their backpack straps, a metal spoon bangs against an industrial pot in a dark kitchen. It’s 4:30 a.m. and the staff at Maruyama Villa are already up and preparing miso soup for the 200 people who slept in the wooden dormitories of the hut the night before.

Outside, the sky was a thin sheet of silver. Inside, steam billows through the restaurant as hikers shuffle in, still half asleep and wearing headlamps. They sat at long communal tables, eating grilled fish and rice, their boots neatly waiting patiently at the entrance. This is Japanese alpine hut choreography that has been practiced for over a century.

Japanese sanso (mountain huts) are part of the infrastructure leading to the Northern and Southern Alps. They are not hotels or basic shelters; they are a rare hybrid – half shelter, half heritage site – maintained by families and staff who live all summer long at nearly 3,000 meters above sea level. Each cabin is different and has its own history, architecture, food culture and responsibilities. Together they form one of the most unique mountain traditions in the world.

Yaro Sanso

Yaritake Mountain Lodge: A hut on the Matterhorn in Japan

From Kamikochi – the peaceful valley in Nagano Prefecture — The classic route to Mount Yarigatake passes by riverside huts and then climbs up the long Yarisawa Valley. Finally, the mountain appears, a slender sliver of rock that separates from the skyline. The 3,180-meter-tall peak has been romantically dubbed Japan’s Matterhorn for decades because of its sharp peak.

Yarigatake Sanso is located less than 100 meters from the top of the mountain and 3,080 meters above sea level. Officially established in 1926, the lodge has become one of the flagship lodges of the series, with a capacity of approximately 400 people and an operating season from the end of April to the beginning of November. Helicopters deliver large amounts of supplies ahead of the main summer season. Afterwards, everything from gas cans to onions would fall on the shoulders of the workers.

Viewed from the entrance, the cabin looks impossibly exposed: a long, low, red-roofed complex hugging the ridge beneath the rocky summit. Since the early Showa era, it has been expanded and rebuilt many times, but its basic functions have not changed. A documentary about the century-old story of the cabin, at the top of the skyexperienced the entire operating season from snowmelt to closure in November.

Inside, the experience is structured. Hikers take off their boots at the door, check in at the front desk, and are led to communal bedrooms separated by low wooden screens and curtains. Dinner is served at set times and usually consists of a plate of rice, miso soup, pickles and a main course – usually a thick Western-style curry or Lin rice, reflecting how the lodges evolved with the growth of mountaineering in the early 20th century and its fascination with the European Alps. Currently, the price for one night with two meals is around 13,000 yen.

As you walk out of the restaurant on a clear night, you’ll suddenly understand why Yaro Sanso has become the backbone of the entire hotel group. The field of view includes the entire Hotaka Mountains, the Tateyama Massif, the Central Alps and the Southern Alps. When the weather is best, you can see Mount Fuji all the way.

Karasawa Cabin

Karasawa Hütte: Autumn at the bottom of the bowl

A few valleys away, the Karasawa Circus puts on a different kind of drama. This is one of the major glacial basins of the Northern Alps and is surrounded by some of the country’s highest peaks. The bottom of the cirque is about 2,300 meters above sea level, about 900 meters from the ridgeline, and about 2 kilometers in diameter. In late summer, there is still snow on the rock walls. The meltwater stream forms the source of the Azusa River that flows through Kamikochi.

The standard route from Kamikochi is a two-day, 30-kilometer round trip with an altitude of about 800 meters. Upon reaching the Cirque, hikers find not a vast expanse of wilderness but two sturdy huts—Karasawa Hütte and Karasawa Goya—and wide gravel benches that, in high season, transform into a “tent city” with hundreds of brightly colored tents.

Karasawa Hütte itself dates back to the mid-1920s, when huts began popping up in the Hotaka Mountains in response to the increasing number of climbers. It operates as a seasonal lodge, usually from late April to early November, and is both a base for Hotaka climbing and a destination for leaf hunters. Inside, you’ll see the familiar mountain cabin layout: rows of futons, low ceilings and a canteen serving hot meals. For non-staying guests, a curry plate or ramen here costs about 1,200 yen; an overnight stay with two meals usually costs around 14,000 yen, in line with other full-service inns in the Alps.

One detail makes the place feel almost surreal: You can sit on the rooftop terrace, surrounded by vertical rock walls, eating beef curry and oden, and drinking draft beer flown in by helicopter, while the entire ice bucket burns red and gold below the line of the first October snow.

At night, cold air can accumulate in the bowl. The sky became extremely clear. When dawn arrives, the ridge changes from pink to yellow, a phenomenon known to German-speaking staff and early European visitors as Morgenröte, or morning red.

nzaso

The Queen of the Northern Alps—Zimbalu Maru Villa

If Yarogatake is a spear and Hotaka is an amphitheatre, then Mount Tsubaru is an invitation. Located in Azumino City, this mountain is approximately 2,763 meters above sea level and is famous for its light-colored granite ridges, white sand beaches, and sweeping views in all directions. The local tourism board promotes it as the “Queen of the Northern Alps”, in contrast to the more severe “King” peaks surrounding it.

The climb from Nakabusa Onsen is steep and direct, climbing a ridge called Kassen-one, ascending approximately 1,400 meters in 6 hours. At the top of the mountain, just below the summit, stands Maruyamaso, one of Japan’s most famous huts. It was built in 1921 by mountaineer Chihiro Akanuma and later expanded into the large multi-story hut it is today.

With a capacity of around 650 people, it is one of the largest huts in the Alps, and all accommodation must be booked in advance. The hut is usually open from mid-April to late November, with a brief opening over New Year’s Day, and there’s even a summer mountain clinic staffed by Juntendo University’s Medical Alpine Club.

Round House is a meeting place of many cabin cultures. It serves as the anchorage for the Omoteso-Ginza Yokoichi, a classic ridge route that stretches from Tsumbakuro to Mount Daitenso and finally to Mount Yari-dake, one of the most famous multi-day hikes in the range. It’s also famous among hikers for its little luxuries: cake packages and draft beers on the terrace, horn shows in the evenings, and almost panoramic views of the peaks—Yaridake and Hotaka, the perennial mountains, and even Mount Fuji and the Southern Alps on clear days.

Morning routine is simple. People wake up around 4 a.m., put on their down jackets and go out to the terrace. Below them, thick inversion clouds often fill Nagano’s valleys. As the sun rises behind the Yatsugatake Mountains, the ridges briefly turn silver and then gold. Breakfast is grilled fish, rice, kimchi, and tamagoyaki. Hikers repack and either continue higher or head back to the hot spring steam and paved roads.

Yaro Sanso

The system behind the summit

Taken together, these huts describe the shape of Japanese mountain culture more accurately than any map can. Their establishment dates back to the early 20th century, the same period in which recreational mountaineering, university climbing clubs, and national park policies were taking shape. Today, their operations still follow the logic of the mountains themselves—operating seasons are determined by snowmelt and typhoon cycles, pricing is influenced by helicopter loads, and reservations are capped not for exclusivity but to keep crowded ridgelines safe.

For hikers, the effect is very simple. You move through forest, rock, and weather all day before arriving at a ridge or a strip of light on the floor of a cirque. Inside there was a row of slippers, a steaming pot of curry on the counter, a handwritten weather board and a bed covered with a folded blanket. At dawn, people went out almost simultaneously to watch the changes in the sky. People with nothing in common outside the mountains shared pallets and boiled their conversations down to their essentials: forecast, route, time.

Japan’s hut system doesn’t soften mountains or turn them into amusement parks. The traces remain severe; intersections such as Daikiretto Gorge between Nanshan and Kitahoteka Mountains are among the most exposed in the country. The role of cabins is quieter: they make these places habitable without making them less difficult. They humanize altitude—a meal, a dry bed, a bit of order in the wind—and in doing so, they intertwine access and safety.

Spend a night in one and you’ll understand why this system has lasted a century. It’s not comfort that keeps people coming back. This is how these cabins allow you to live briefly and dignifiedly in terrain that would otherwise drive you out.

Anal Beads

Anal Beads Anal Vibrators

Anal Vibrators Butt Plugs

Butt Plugs Prostate Massagers

Prostate Massagers

Alien Dildos

Alien Dildos Realistic Dildos

Realistic Dildos

Kegel Exercisers & Balls

Kegel Exercisers & Balls Classic Vibrating Eggs

Classic Vibrating Eggs Remote Vibrating Eggs

Remote Vibrating Eggs Vibrating Bullets

Vibrating Bullets

Bullet Vibrators

Bullet Vibrators Classic Vibrators

Classic Vibrators Clitoral Vibrators

Clitoral Vibrators G-Spot Vibrators

G-Spot Vibrators Massage Wand Vibrators

Massage Wand Vibrators Rabbit Vibrators

Rabbit Vibrators Remote Vibrators

Remote Vibrators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators

Pocket Stroker & Pussy Masturbators Vibrating Masturbators

Vibrating Masturbators

Cock Rings

Cock Rings Penis Pumps

Penis Pumps

Wearable Vibrators

Wearable Vibrators Blindfolds, Masks & Gags

Blindfolds, Masks & Gags Bondage Kits

Bondage Kits Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing

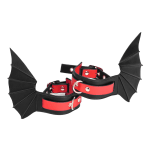

Bondage Wear & Fetish Clothing Restraints & Handcuffs

Restraints & Handcuffs Sex Swings

Sex Swings Ticklers, Paddles & Whips

Ticklers, Paddles & Whips